A small landmark of New York

City architectural and automotive history disappeared

recently, almost without notice. The theatrical auto

showroom designed by Frank Lloyd Wright at 430 Park Avenue,

at 56th Street, had displayed a number of European brands

over the years, notably Mercedes-Benz from 1957 to 2012.

The space, with a spiral ramp and turntable interior, was

designed in 1954 for the pioneering auto importer Max

Hoffman.

|

|

The

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum

of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts

Library, Columbia University, New York) |

|

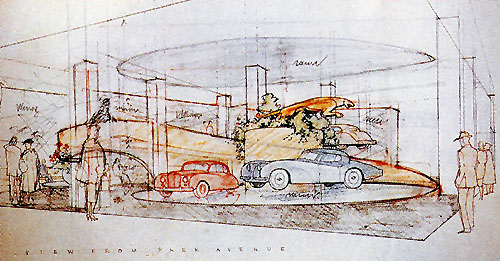

Frank Lloyd Wright's sketch of the Hoffman

automobile showroom at 430 Park Ave. |

In early April, the Wright interior was demolished by the

owners of the building, Midwood Investment and Management

and Oestreicher Properties. Debra Pickrel, a preservationist

and co-author of “Frank Lloyd Wright in New York: The Plaza

Years, 1954-1959” (Gibbs Smith, 2007) wrote about the

showroom’s destruction in Metropolis magazine.

Born in Austria, Maximilian Hoffman immigrated to New York

with the outbreak of World War II. In 1947, he established a

firm to import little-known European brands to New York and

the West Coast.

Hoffman first intended the showroom for Jaguars. Drawings

from the Wright archives show a leaping Jaguar sculpture and

planters. But by the time the showroom was completed, Jaguar

had set up its own sales space. Instead, the Hoffman space

was filled with a mix of cars, including Porsches, for which

he was the official importer to the United States.

The first drawings for the showroom have pedestrians on Park

Avenue looking into the space. A rotating turntable held

three or four cars; a ramp behind it accommodated one or two

more. That spiral anticipated the design of the Guggenheim

Museum, which opened in 1959.

The showroom was never considered a major work. In 1966, the

architecture critic of The New York Times, Ada Louise

Huxtable, who died in January, referred to it as “cramped.”

But it was one of a handful of Wright buildings in the New

York area, and its form has a definite place in key themes

of Wright’s work, according to historians like David G.

DeLong, professor emeritus of architecture at the University

of Pennsylvania.

Part of Wright’s fee for the design work was two

Mercedes-Benzes, according to Douglas

Steiner, who has written extensively about the

architect. Wright also designed a house for Hoffman in Rye,

N.Y.

Almost alone, it seems, Mr. Hoffman saw a market for

European luxury models in New York and Beverly Hills.

Beginning in the late 1940s, he imported a wide range of

brands, including Delahaye and Austin.

He was willing to take a chance on the former Third Reich’s

people’s car, the Volkswagen, which eventually became a huge

hit. He also offered the Jowett Jupiter, which was not.

Hoffman met Ferry Porsche, son of the company’s founder, in

1950 and began importing Porsches to New York. He often

raced cars himself to publicize the brands. Hoffman was

known for coming up with ideas for new models that would

sell well in the United States, suggesting the series

production of the Mercedes 300SL Gullwing and the Porsche

Speedster to their respective manufacturers.

In 1958, Mercedes-Benz bought out Hoffman and remained in

the Park Avenue space, through two renovations, until

decamping last year for a larger showroom in a new

dealership on Eleventh Avenue.

To students of Wright’s work, the showroom ramps recall

larger designs. One was the never-built Gordon Strong

Automobile Objective, a mountaintop tower imagined in 1924

for a wealthy client. It was to be a structure where cars

would park at the culmination of a scenic drive in Maryland.

The other is the Guggenheim Museum, which resembles the

Automobile Objective tower flipped on its head.

Janet Halstead, executive director of the Frank Lloyd Wright

Building Conservancy, a Chicago-based group dedicated to

preserving Wright’s work, said that after learning of the

planned demolition last June from one of its members, her

organization tried to have the city designate the showroom

as a landmark.

“We have a network of members and professionals who

informally monitor Wright buildings in their regions and in

the media, and we often learn about situations through these

‘Wright watch’ participants,” she said. “They constitute a

kind of early-warning system for risks to Wright buildings.

We sent a formal request for evaluation to the New York City

Landmarks Preservation Commission in August 2012.”

According to Matt Chaban of Crain’s New York Business, who

reported on the events, on March 22 the commission called,

and on March 25 sent a letter, informing the building owner

that landmarking was under discussion.

On March 28, the owner applied to the city Buildings

Department, a separate agency, for a demolition permit,

which was granted. Demolition took place the next week.

“The Landmarks Commission was unaware that the space had

been demolished until we had an eyewitness report that the

space had been gutted,” Ms. Halstead said.

Calls and e-mails to the owners, Midwood Investment and

Management and Oestreicher Properties, and to the building’s

managers, were not returned.

The conservancy’s president, Larry Woodin, issued a

statement reading in part, “It is very disappointing that

the City of New York was not able to move quickly enough to

prevent the demolition of this Wright space.”

Donna Boland, a spokeswoman for Mercedes-Benz, said the hope

when Mercedes left was that the showroom would be leased to

another car company. “We were shocked at the removal,” she

said, “but had no say in it since we leased the space.”

|