|

Growing Up Wright

by Jaimee Rose

March 14, 2009

The Arizona Republic

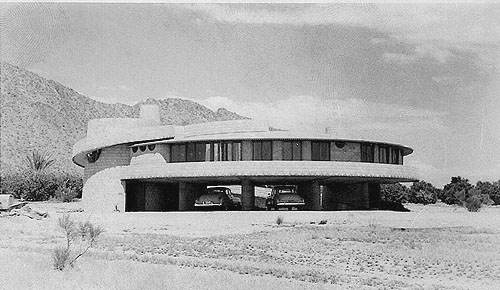

The house has its back to the street.

A circle on a street of squares, it is curled away from the

world, keeping secrets.

It still says "Wright" on the mailbox. Tourists like to pose

next to it and take pictures, entranced by the old-fashioned

black stick-on letters that seem to say it all.

For 57

years, this was the Arcadia home of David and Gladys Wright.

They had movie stars over for dinner, Japanese architects

over for tea and their three granddaughters over for graham

crackers and lemonade. In later years, the Wrights kept to

themselves, shooing tourists away from the orchard and

rerouting buses from the front drive.

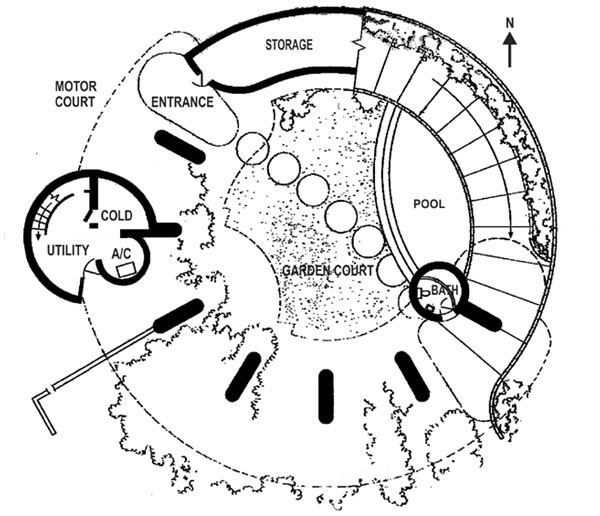

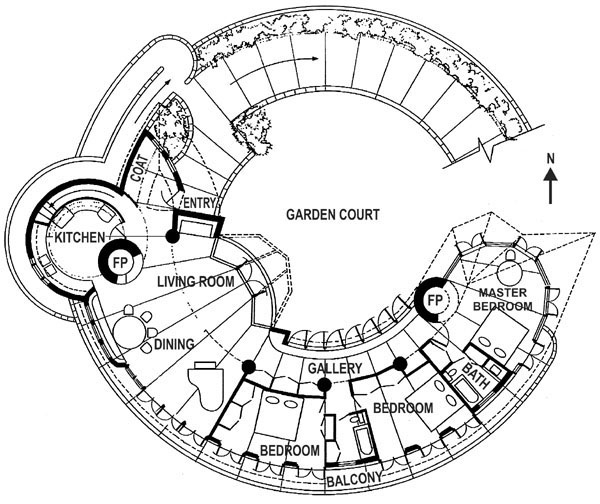

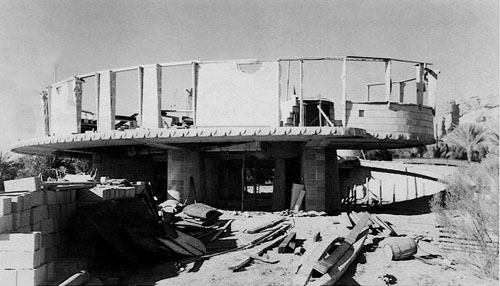

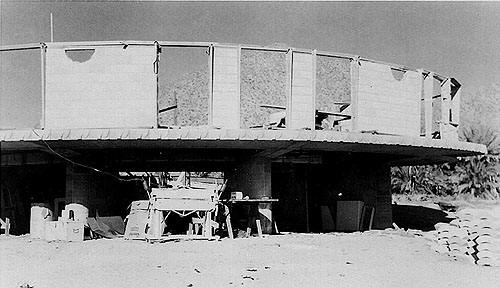

Of the hundreds of homes Frank Lloyd Wright designed, just

two were for his children. One is in Maryland, and this is

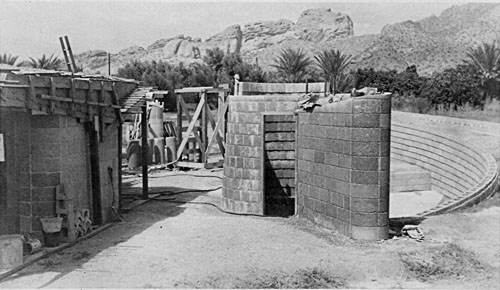

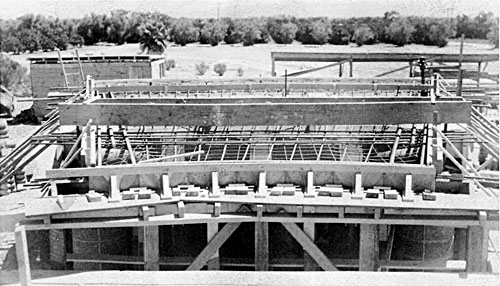

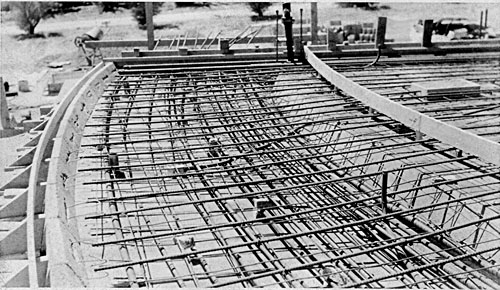

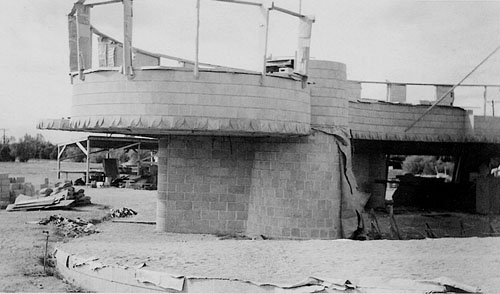

the other, a 1951 spiral design crafted from concrete block

and nestled in the Valley's citrus groves.

David - Frank's son - lived in the house until he died at

age 102. His wife, Gladys, died last year at 104. They

outlived their only son. Their three granddaughters have

listed the house for sale for $3.5 million. To the busloads,

the cameras and the curious, this isn't a home so much as an

homage. David honored his famously fussy father, leaving the

home pristinely original, right down to the custom-made

kitchen trash can.

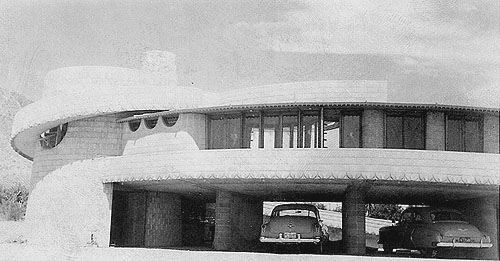

The house is an important piece of the Frank Lloyd Wright

oeuvre, spiraling up like the Guggenheim to let breezes

through, lifting the living room above a canopy of citrus

trees that Frank called the lawn. This house, Frank said,

was how to live in the desert.

Admirers walk through and note the original rug, woven with

Frank's trademark bright circles and lines. They sigh over

the dining-room table and Frank Lloyd Wright-designed

chairs, which convey to the next owner. The lucky ones get

to glimpse Frank's careful, blocked handwriting on the house

plans, which are stored in the closet. Even Gladys' pink

shag toilet-seat cover is intact.

But to David's three granddaughters who grew up next door,

this was Grandma and Grandpa's house, imbued with a

different sort of magic. The kitchen always smelled like

citrus. That geometric rug Great-Grandpa designed made the

best racetrack for toy cars. And those famous end tables are

beloved because Grandma's homemade chocolate birthday cakes

were always served on top.

This is the home of a family - a normal family with memories

both happy and hard that lived in a famous house with a

famous name on the mailbox and a famous patriarch that made

the world more lovely but family life tough.

"People lived there," says Ann Wright-Levi, one of David's

granddaughters. "I think my grandfather knew what they had

there, that it is a legacy.

"There are memories there of growing up and running through

the grove and having family get-togethers for holidays,"

says Wright-Levi, 50, of Phoenix. "My kids remember Grandpa

(David) dancing around on the carpet with them, and standing

on his feet, the piano playing."

"We didn't really know who Frank Lloyd Wright was," says

Kimberly Lloyd Wright, 52, Ann's sister, "that he was this

renowned, famous architect."

"To us, it's just a home," says Karen Robertson, 47, the

third of David's granddaughters. "We grew up in it."

Life as a Wright

Being one of Frank Lloyd Wright's great-granddaughters means

the following things:

You have divine inherited furniture. You grew up with

"Lloyd" as your middle name, when all the other girls were

Gayle and Marie. And you have a legacy as belligerent as it

is brilliant. Frank was known for his cantankerous, picky,

self-important streak. These traits conveyed.

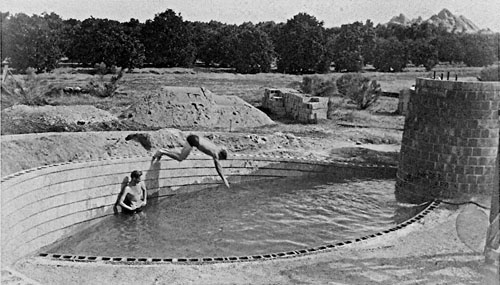

Even David required appointments for their visits. Mind you,

they lived next door. In the house, they weren't allowed

past the living room. "We didn't have refrigerator rights,"

Kimberly says. And if they wanted to go swimming with

Grandma, bathing caps were required.

"God forbid I break her butter dish," Kimberly says. "She

(didn't) even have a TV."

Living in a Frank Lloyd Wright house can mean the following

things:

Your roof leaks. A lot. (From Gladys Wright's diary, dated

July 27, 1952: Heavy rain in the evening. Many leaks.) If

Frank ever came to visit, "he would come in and rearrange

everything the way he wanted it, and as soon as he'd leave,

they'd put it all back again," Karen says.

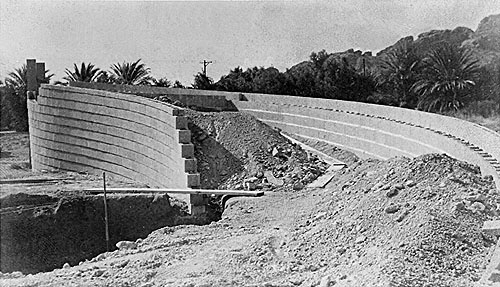

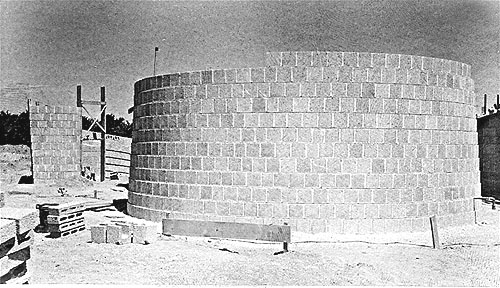

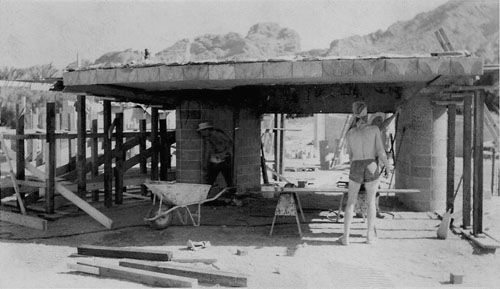

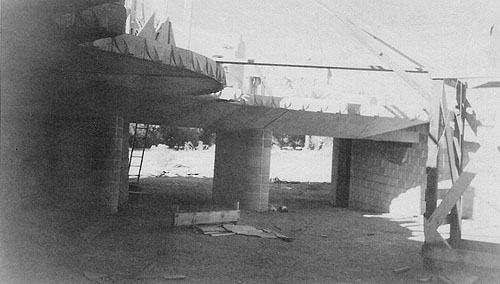

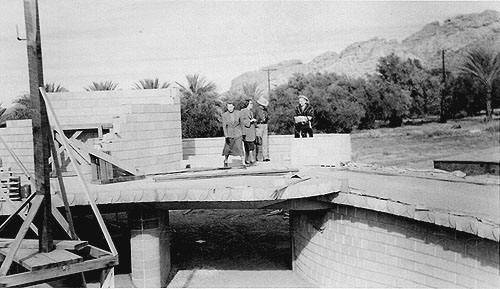

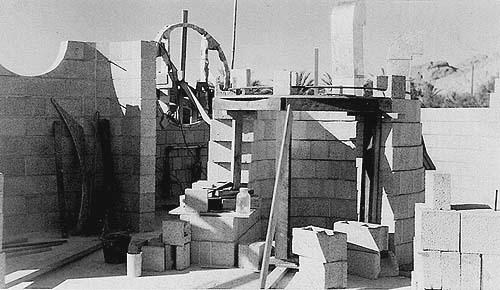

And in building the house, you had to deal with Frank

himself. An arduous task, even if he is your father.

David and Frank wrote many letters back and forth during the

1951 construction. The originals are now for sale through

Alcuin Books in Scottsdale for $40,000. Those letters and

Gladys' only remaining diary, which covers 1950-54, share a

glimpse into life constructing and living in this house.

A letter dated Sept. 14, 1950, from David to his father

reads:

You have me wondering if I am wrong in assuming that you are

planning a house for Gladys and David Wright . . . I want a

Frank Lloyd Wright house, you may be sure, but I don't want

a house worked out on a general plan, adaptable as an idea.

90% Frank Lloyd Wright but 10% for Gladys and David Wright

would be about the right proportion . . .

On Sept. 23, Frank wrote back:

Dear Dave: You make your old father tired.

Kimberly, the eldest granddaughter, has one photo of herself

with Frank before he died. She's a baby, and he is pointing

his finger at her.

"He looks mean," she says, laughing.

Man of the house

David and Gladys weren't the kind of grandparents that

cuddled and coddled, the sisters say. They both had

difficult childhoods.

Frank left his first wife - David's mother, Catherine - and

went abroad with Mamah Cheney. (Their love story inspired

the recent best-seller "Loving Frank.") The sisters say he

told a teenage David that he was now the man of the house.

"We didn't have all the warm fuzzies," Kimberly says. But in

small ways, they felt their grandparents' love. Gladys made

all their doll clothes and baked those birthday cakes.

"One day, I caught them holding hands," Kimberly remembers.

The girls' father was Gladys' only son. He died when the

girls were teenagers.

"When he passed, (Grandpa) was devastated," Kimberly says.

"He promised my father that he would take care of us, but he

was very devastated."

David and Gladys liked life just so: "Hamburgers on Monday,

hot dogs on Tuesday, Grandma went to the grocery store on

Wednesday," Karen remembers. Grandpa cooked and carved the

Thanksgiving turkey every year. There was even a right way

to water the trees and a wrong way, and much ado was made of

both.

"It's genetic," Kimberly says, giggling. In David and

Gladys' house, Frank built the headboards into the walls, so

that the beds would always face the way he imagined. He

built all the furniture because he hated to see someone

else's ideas inhabiting in his design.

From Gladys' diary, dated Jan. 30, 1952: Out to see Father.

I wonder just whom this house belongs to.

Life in Phoenix

"My grandfather didn't care what his father thought," Karen

says. But David and Gladys sure loved that house.

(Gladys' diary, dated Dec. 15. 1951: Out to see progress on

house - beautiful in moonlight. So calm.)

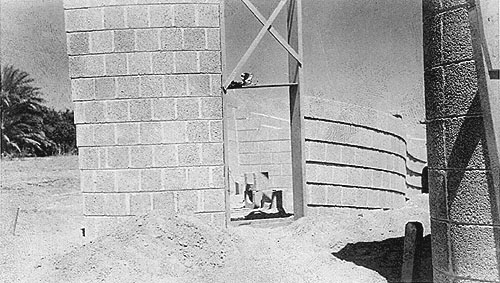

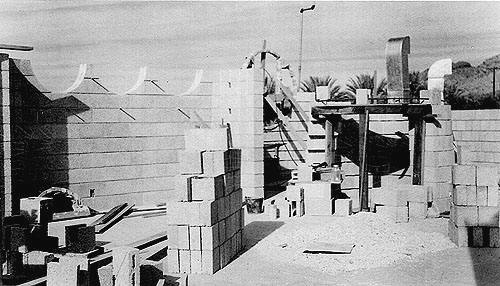

Frank had conceived the home to be built of wood, but David

was a principal at Besser Block and asked that it be

constructed of concrete blocks instead. This, he felt, made

it "his Taj Mahal," his creation as much as his father's,

Karen says.

In the beginning, David and Gladys were anxious to show off

the house. Gladys kept a leather guest book engraved with

"The Wrights" in gold. It comes with the house.

"It was open season." Karen says. "Anyone could come in."

Movie star Anne Baxter came to stay with them. She was one

of Frank's granddaughters. There were architects from Japan

and Taliesin, Frank's estate in Spring Green, Wis. House

Beautiful came and did a write-up, calling the home a

"modern castle in the air" and "one of the most exquisite

examples of the romance and beauty (Frank) has brought . . .

to American life."

Gladys and David lived worthy of such a home. Her diary is

filled with dinners at El Chorro and Macayo's, lunch at the

Camelback Inn, new red shoes. She worries over whether to

join a country club, then reports on symphonies and

cocktails at the Biltmore with Frank in a rare "charming

mood."

Jan 28, 1951: Are we popular? Finally home all a date

straight. Snowing again. Ate too much.

Letting go

Things changed when their father died at age 49, the sisters

say, leaving their grandparents quiet and broken-hearted.

They tired of the tourists, the magazines, the attention.

"Grandma would say, 'I can't go to dinner. The media will

find out that I'm going to be out,' " Kimberly says.

Frank had died in 1959, and David asked the architects at

Taliesin West to stop calling about tours.

"This (house) was their life," says Karen, who cared for her

grandparents in their later years. "They never left it, and

they never wanted to. They wanted to live and die in their

home."

It would be hard for the sisters to live there today, they

say. There are too many memories and too little closet

space.

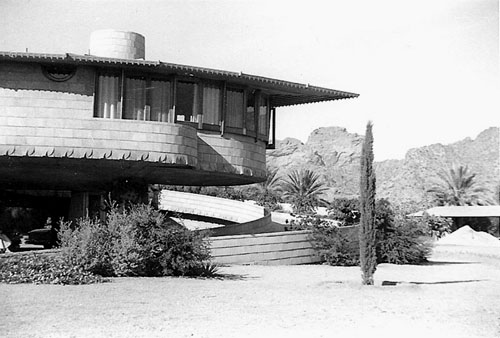

The glory of the house is that nothing has been renovated in

57 years. This means feeling Frank's spirit but also a dark

master bathroom the size of today's walk-in pantries. There

isn't a speck of granite or travertine. The ceiling,

cabinets and furniture are all made of Philippine mahogany.

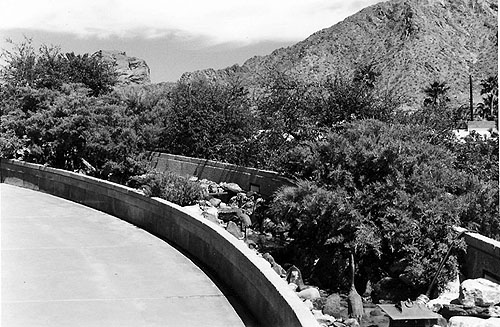

The house's glass windows curl around a precious view of

Camelback Mountain and a courtyard decorated with jasmine

and bougainvillea. David and Gladys liked to pose there for

pictures.

The sisters decided together to let the house go.

"I love the architecture," says Kimberly, whose Scottsdale

home is filled with pieces from her grandparents' life,

including screens from Japan and a ship Frank dragged back

from his travels. "I would love to have a Frank Lloyd Wright

home. But it would have to be me. This is Grandma and

Grandpa."

Ann still comes by sometimes and walks her dogs through the

orchard, where she used to play as a girl.

"There's a feeling there," she says. "I haven't quite put my

finger on it. I think it's kind of bittersweet, thinking

that they're not there and that someday, somebody else might

be." |