NOW AVAILABLE

CLICK TO ORDER

Dr. Toufic H. & Mildred Kalil Residence, Manchester, NH (1955 - S.387)

In the fall of 2007 I had the opportunity to tour the Zimmerman home. Because of the close proximity (only a half a block), we also took the time to visit the Kalil home. The Zimmerman home, designed in 1950, was completed in 1952. The Kalils were associates and friends of the Zimmermans. There is no doubt that the Zimmerman's new home and their friendship influenced them to contact Wright. On July 1, 1954 the Kalils began their correspondence.

Not much has been written about the Kalil Residence. But Michael Komanesky has written a detailed article on "Morton Delson and The Kalil House". Dr. Kalil's parents immigrated to Manchester, an industrial hub at the turn of the century. Toufic was born in Manchester in 1907. He remained in Manchester and opened practice there. He married Mildred in 1940, and fourteen years later contacted Wright.

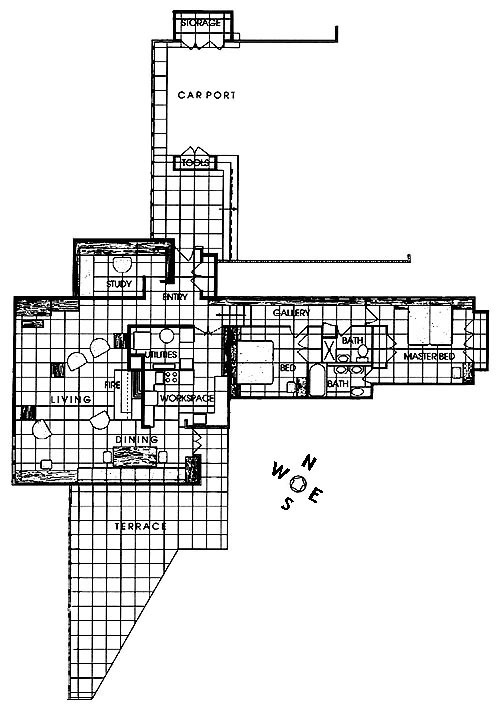

Wright used concrete blocks in many of his homes. But this was only the fourth Usonian Automatic home built using concrete molded blocks. (Adelman S.344, Pieper 349, Tonkens 386, Kalil 387, Turkel 388, Tracy 389 and Pappas 392). Others were designed using this method, but constructed of standard concrete blocks. If the Kalil home looks similar to the Tracy Residence (S.389), its because the same molds were used in both homes. Not only are the overhead blocks two foot square, but the home is built on a two foot square grid system, which is consistent with the other homes built of this style. The vertical wall blocks measure one foot by two feet.

John Howe drew the presentation drawings. Chris Besinger was responsible for the working drawings. Camillo Palermo and his partner became the general contractors that oversaw construction. John Martineau and Louie LaTullipe worked for Palermo and worked on the home for two years. MortonDelson was Wright's on-site apprentice.

To automate production of over twenty different block designs, Dr. Kalil had a machine built that created each block under pressure, allowing the blocks to be removed from their forms immediately enabling the start of the next block. Construction began in 1955 and the home was finished in 1957 at a cost of between $70,000 to $80,000, much higher than the $25,000 to $35,000 that was first estimated.

Dr. Kalil passed away in October 1990. Mrs. Kalil had passed away a few years before him. The home was passed on to Dr. Kalil's brother John, who continues to live in the home.

There are many classic Wright details. The basic materials are concrete blocks, Philippine mahogany and a Cherokee red poured concrete floor with radiant heat. It is designed on a two foot grid. There are rows of perforated concrete blocks with embedded mitered glass corners. There are perforated concrete block windows and clerestory windows with embedded glass. A centrally located sunken fireplace. Clerestory windows bring light into the interior Workspace. The hidden entrance, but this door actually opens inward. And the carport. Like many of Wright’s homes, he designed the built-in seating and shelving, many of the fixtures and some of the furniture.

The 1,380 square foot home has a living room, kitchen, two bedrooms, two baths and a study. The interior is trimmed and paneled throughout in Philippine mahogany. All of the original furniture, most of which is built-in, still exists. Not only tables and chairs, but also fabric items: the autumn-toned bedspreads, the upholstery, and the 30 throw pillows overlapping each other along the living room couch.

There is also an unfinished mother-in-law house on the property.

September 2007FLOOR PLAN PHOTOGRAPHS INTERIOR 2005 EXTERIOR 2007 BUILDING KALIL HOUSE USONIAN AUTOMATIC TRAVELING EXHIBIT RELATED BOOKS FLOOR PLAN PHOTOGRAPHS Date: Circa 1959

Title: Dr. Toufic H and Mildred Kalil Residence, Manchester, New Hampshire, Circa 1959 (1955 - S.387).

Description: Viewed from the North as you approach the house from the street. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1955. This was the fourth Usonian Automatic home built using concrete molded blocks. Label pasted to board: "Arch. U.S.A. 20th cent. Frank Lloyd Wright. Res. T.H. Kalis, Manchester, N.H. (1957). Entrance. Wayne Andrews #2120. Indiana University, Fine Arts Department." Photographed by Wayne Andrews. Acquired from the archives of the Indiana University.

Size: Original 9.5 x 7.5 B&W Photograph.

S#: 1377.128.0920Date: 2007

Title: Dr. Toufic H and Mildred Kalil Residence, Manchester, New Hampshire, 2007 (1955 - S.387).

Description: Set of 13 photographs of the Kalil Residence. There are many classic Wright details. The basic materials are concrete blocks, Philippine mahogany and a Cherokee red poured concrete floor with radiant heat. It is designed on a two foot grid. There are rows of perforated concrete blocks with embedded mitered glass corners. There are perforated concrete block windows and clerestory windows with embedded glass. A centrally located sunken fireplace. Clerestory windows bring light into the interior Workspace. The hidden entrance, but this door actually opens inward. And the carport. Like many of Wright’s homes, he designed the built-in seating and shelving, many of the fixtures and some of the furniture. The 1,380 square foot home has a living room, kitchen, two bedrooms, two baths and... Continue...

Size: Set of 13 high res 10 x 7.5 color photographs.

ST#: 2007.93.0920 (1-13)

See additional photographs...

See additional photographs...INTERIOR PHOTOGRAPHS BY GEOFF FORESTER, JULY 2005

The Wright neighborhood

New England has few of the master's works, but two share a street in New HampshireThe Boston Globe

July 7, 2005

By Jenny Donelan, Globe Correspondent

Photographs by Geoff Forester, Globe staff photographer

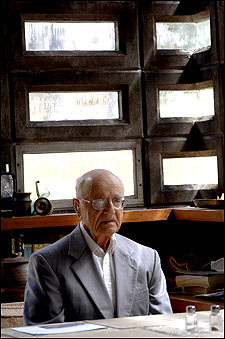

Homeowner John Kalil, 89, says he plans to sell the Frank Lloyd house he inherited to a buyer who wants to live in a "Wright home." (Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester) MANCHESTER, N.H. -- Most of the 250 Frank Lloyd Wright structures that remain as private residences are inhabited by Wright devotees, people who either commissioned their homes from Wright himself, or who excitedly bought their own piece of live-in history.

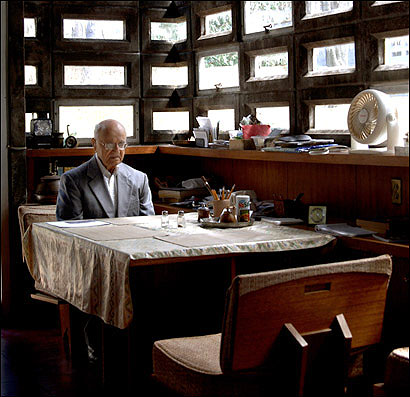

John Kalil, 89, a retired civil engineer who's lived in his Wright house for 15 years, isn't one of those.

''I like it fine," is about as close as he gets to gushing about the place. ''It isn't the type of house that's closed in. It gives you a feeling of being free."

Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester

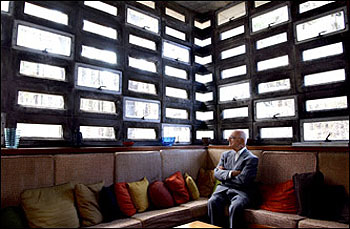

John Kalil, who inherited the Frank Lloyd Wright house from his brother, has lived in the house in Manchester, N.H. for 15 years. Here, he sits in his favorite area: the corner living room. Perhaps his reserve is constitutional, though it also may stem from how he came to live here. Far from pursuing the Wright dream, the house came to him, by inheritance; his brother, Toufic H. Kalil, was the devotee. When Toufic commissioned the house in the 1950s, John didn't know much about Wright ''other than that he was a famous architect," he says.

But Toufic knew the Zimmermans --whose Wright house a couple of doors away is now owned by the Currier Museum of Art -- admired their home, and ''didn't like any other kind," according to John.

This isn't to say that John isn't conscious of the artistic and historic importance of his home. He's working to preserve it, and when he eventually sells it -- it's not on the market -- he wants the buyer to be ''somebody who wants a Wright home." In this, he resembles the majority of Wright homeowners, who, in the words of Ron Scherubel, executive director for the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy in Chicago, ''know exactly what they have and have a strong feeling that we need to preserve this for future generations."

Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester

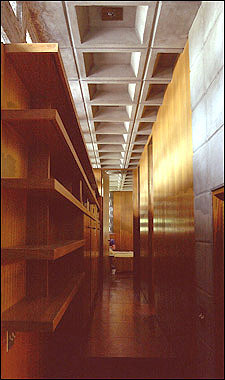

Inside, the house is paneled in Philippine mahogany. The main hallway leads to the bedroom. Kalil shares something else with a number of Wright homeowners: his age. Though Kalil still drives, does his own yard work, and manages as many household duties as people half his age, a number of the folks who commissioned Wright homes in the 1940s and 1950s are getting to the stage where they are moving beyond single-family home life.

The 1,380-square-foot house that was built for Toufic in 1955 is an example of Wright's Usonian (for United States of North America) designs, which were meant to provide exceptional housing for people of mid-range incomes.

Although it seems odd that the only two Wright houses in New Hampshire (out of only five in all of New England) share the same street, it's actually not all that unusual to find Wright houses in clusters, notes Hetty Startup, Zimmerman House administrator at the Currier and vice president of education and outreach for the Wright conservancy.

In some cases, as in Usonia in upstate New York, the grouping was planned; in others, as in Manchester, it occurred naturally. Zimmerman and Toufic Kalil worked together as doctors at Sacred Heart Hospital in Manchester, and both were Wright fans. ''The coincidence is that a piece of land came up for sale just down the street from the Zimmerman House rather than elsewhere in the city," says Startup.

Although Wright drew up and approved the plans for the Kalil House, he never visited the site; his practice was to send an apprentice to supervise building, and Morton Delson was his man in Manchester.

The Kalil House is a ''Usonian Automatic," meaning that it's built of concrete blocks that homeowners, theoretically, could make themselves. In reality, few homeowners did. For the Kalil House -- which cost between $70,000 and $80,000, no small figure in 1955 -- the blocks were created by Manchester Sand and Gravel. Like most Usonian dwellings, the house has few windows facing the street but many more facing the back, toward the terrace, trees, and grass, so as to integrate its occupants with nature.

Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester

Evidence of stains from acid rain can be seen in the kitchen. Inside, the house is paneled throughout in Philippine mahogany, including the specially treated walls of the sunken tub-shower. Much of the furniture, including the bookshelves, is built in. The effect in the bedroom/study/hall is a bit like a well-designed camper or boat -- so much has been so cleverly fit into a relatively small space. By contrast, the living room, with a central fireplace and a virtual wall of small windows, is airy and spacious.

People who visit sometimes ask Kalil what his favorite part of the house is. ''Right there," he tells them, pointing to the corner where the two lengths of the built-in living room couch meet below windows open to the yard in back. Everyone seems to be drawn to that spot, he says.

Occasionally, strangers are drawn to the house itself, which does stand out, especially in northern New England. Kalil, who values his privacy, has had to ask people taking pictures to leave. Fortunately, he says, he can tell them there's the Zimmerman House up the road, which is open to the public by reservation.

Most homeowners don't have to contend with the shutterbugs, but they all have to deal with maintenance, and that includes Kalil. Although he says the house isn't difficult to maintain, he sometimes has to devise creative solutions.

''You're living in a house that needs to be kept up like any other," says Startup. ''But you're also living in a house that is designed by America's foremost architect. And you're living in a finite object. There aren't any more of them."

Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester

The Kalil House is a "Usonian Automatic," meaning that it's built of concrete blocks that the homeowners, theoretically, could build themselves. This is a photo of the entrance to the dining room. For one, Kalil's home contains the kind of original furnishings many Wright homeowners only dream of -- not only tables and chairs, but also fabric items: the autumn-toned bedspreads, the upholstery, and the 30 throw pillows overlapping each other along the living room couch. Sometimes keeping everything in shape requires an expert, such as Debora Mayer, a Portsmouth, N.H.-based paper specialist who repaired some lampshades in recent years. But to keep the upholstery in good condition, says Kalil, he hires cleaners right out of the phone book.

Other maintenance issues are trickier. For example, acid rain and the freeze-thaw cycle have taken their toll on parts of the Kalil House's exterior concrete blocks. So far, Kalil has been dissatisfied with at least a couple of contractors: The first used the wrong materials, he says. The second did passable work but then plastered over the concrete, at which point Kalil removed him from the job. He is currently looking into another company to do the work.

''There are real preservation dilemmas," says John Payne, who with his wife, Edith, lives in the Richardson House, a Wright design in Glen Ridge, N.J. The couple recently spoke at a Zimmerman House docents' training in Manchester about the issues of maintenance and preservation; they were available because, at the time, they'd moved out for several months while extensive repairs were being done.

Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester

Condensation builds up inside the windows of the house. Among the repairs at the Richardson House are replacement of the radiant heating system -- pipes embedded in the concrete floor of the house (typical for Wright houses). Because of a chemical reaction between the pipes and the concrete over time, the pipes have ''turned to lace," according to Edith Payne, and so the entire floor must be jack-hammered apart, the pipes replaced, and a new floor poured. The original floor, or most of it, will be lost.

But the alternative would have been to add baseboard heating, which would have greatly altered the design intent of the house. Such are the decisions faced by Wright homeowners.

It can be a tough call, and though the majority of Wright buildings aren't subject to any special regulations when it comes to home improvements, the conservancy (savewright.org) offers support and guidance to Wright property owners as if they were.

Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester

The dwelling features a detached in-law apartment. Kalil, who is aware of the organization, says he's not interested in joining. Though the word ''stewardship" certainly describes the role Kalil is playing -- the term comes up a lot among Wright owners -- he seems to want to get the job done more than discuss it.

The concrete work and a dehumidifier are in the home's short-term future, says Kalil. In the longer term, he will sell it (he has no heirs) but has no idea when. Kalil is also not sure what the house is worth. It sits on three-quarters of an acre with a view of distant mountains and has a in-law apartment in back that Kalil uses for storage. The houses in his neighborhood are quite diverse, with homes that look like mansions sharing the streets with modest ranch houses and former farmhouses. Property values vary widely. ''A conservative average," says Christine Gagnon, a real estate agent with ERA The Masiello Group in Manchester, ''is $350,000 to $400,000." She said the neighborhood is quite ''desirable."

Globe staff photo/Geoff Forester

Homeowner John Kalil, 89, says he plans to sell the house to a buyer who wants to live in a "Wright home." A Wright house is sometimes easy to sell, sometimes not. Location and condition factor into the sale

as they would for any house, says the conservancy's Scherubel. ''Generally speaking," he says, ''there is a premium, but it's not usually as much as the owner wishes it were, usually 10 percent to 20 percent over the market price for comparable houses in the area."

A recent roster of Wright houses listed for sale on the conservancy's website ranged from $375,000 for the Eric Pratt House, a three-bedroom Usonian in Michigan, to $2.5 million for the Andrew B. & Maude Cooke House, a waterfront estate in Virginia.

The Kalil House is on the small side, but its location in a good neighborhood in an urban center and its plethora of original furnishings -- down to the kitchen appliances -- could make it especially desirable to Wright aficionados.

One thing is for certain: Kalil would like to see the house end up in the hands of people who recognize it for what it is.

When asked how he would feel about someone buying the property for the land alone and doing away with the house -- a fate some Wright homes have met, or almost met -- he says with alarm and not a trace of irony, ''That wouldn't be right."

EXTERIOR PHOTOGRAPHS BY DOUGLAS M. STEINER SEPTEMBER 2007 "We worked on this house for over two years."

My Story of Building Dr. Kalil’s House in Manchester, NH.

Written by Paul Beaudoin as told to him by his father-in-law John Martineau, January 2007.My name is John Martineau, and I have lived in Methuen, MA all my life. As a young man I was learning the masonry trade and was employed by Carmen Palermo. I joined a fellow classmate, Louie LaTullipe, who was already employed as an apprentice. During 1953 (1955), the contractor was contacted by Dr. Kalil to build a new type of concrete house, in Manchester, NH, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The style of this house was called Usonian. We worked on this house for over two years.

The first time I went to the job site the foundations had already been poured. We were starting to do the walls, which were special custom made blocks. The forms for the blocks were made by a local welding shop. The blocks were poured by Duracrete. All of the electrical outlets and other utilities needed to be considered for each of the blocks. Frank Lloyd Wright’s designed called for two foot square blocks, a very common theme in all his houses. One very critical mistake that was overlooked was that when the forms were made, they were made to exact dimensions, with no consideration made to take into account the mortar joints, or any “out-of-square” that occurred during the pouring of each block.

Mr. Palermo was the type of contractor that had a very “can-do” attitude. As he started to take his measurements, he quickly realized that because of the accumulated tolerances, the blocks were going to quickly make the walls too long. Also, none of the horizontal or vertical joints were going to line up.

An engineer was making monthly visits to check on the progress. After obtaining approval from the engineer, a jig was made to shave all of the blocks down to a more accurate working dimension. Mr. Palermo devised a jig that consisted of two engines with giant grinding wheels that sat on either side of a roller conveyor. Each block had to be passed through twice for all four sides to be ground evenly.

As the walls were being built, all of the electrical wiring had to be run at the same time. Now, Mr. Palermo was not an electrician, but he knew enough about wiring to get it done. He stated that “if we couldn’t figure it out, we could go to the public library and find out how”. The wiring was a very long process. Each wire had to be brought up through the wall as the wall was being built.

The pouring of the colored concrete (red) floors, uncovered other new problems. Every time we tried to cut the joint lines, (to create the two foot square symmetrical pattern), the stone aggregate would poke through destroying the smooth trowel finish. We needed to get approval from the engineer to cut the joint lines with a diamond saw blade after the floor cured.

The roof took an unbelievable amount of labor to complete. Each of the blocks had to be kept square to each other, proper height from the floor, and perfectly level. Each of the blocks had to be supported until after each of the two rods was inserted. Each of the blocks weighed between 180 and 220 pounds, depending if they were solid or with an imbedded pattern.

Each of these blocks was wheeled up a ramp to the roof. One guy would balance the wheel-barrel and the other guy would pull the wheel-barrel by rope.

The roof also had a cooling feature that allowed the roof to be flooded to keep the house cool in the summer. The corners of the roof had a drain plug to retain the water, but allow an overflow to drain. After the blocks of the roof were completed, a fiberglass blanket was laid down for water proofing. This was a new type of material that was being used, for the time.

We were unconvinced that the roof of the carport would be able to withstand the load of holding itself up. The carport roof was cantilevered with a trussed rod support system. We were very unsure to step on the carport after it was done.

After the fireplace and chimney were completed, there appeared to be some kind of a draft problem. We needed to insure that the flue linings were correctly sealed. I volunteered to be lowered down into the chimney by rope. Where I trowel sealed all of the flue linings. I didn’t leave any “gifts”, though. The real problem was that the house had been designed and built too airtight. So tight that no draft could be created for the fireplace.

Sadly I never got to see the house completed. A special Philippine mahogany was ordered for the finish woodwork.

In my opinion, the house was not very economical or very practical.

Written by Paul Beaudoin as told to him by John Martineau, January 2007. Paul, John’s son-in-law, lives in Derry, New Hampshire with his wife Phyllis, the daughter of John Martineau. John lives in Methuen, MA, is currently enjoying his retirement and still lives in the house that he built in 1963.

Usonian Automatic Homes (Built)

Usonian Automatic Traveling Exhibit Related Books

"Frank Lloyd Wright, His Life and His Architecture" Twombly, 1979, page 338 "Frank Lloyd Wright: In The Realm of Ideas" Pfeiffer, Nordland, 1988, page 72. "GI 10: Global Interior #10: Houses by Frank Lloyd Wright 2" Text: Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks; Edited and Photographed: Futagawa, Yukio, 1990, pages 164-169. "Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph 1951-1959", Text: Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks; Edited and Photographed: Futagawa, Yukio, 1990, page 182-183. "Frank Lloyd Wright Selected Houses 8", Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks, 1991, page 174-183. "Architectural Monographs No 18: Frank Lloyd Wright" Heinz, 1992, page 134. “The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion”, Storrer, William Allin, 1993, page 415. "Frank Lloyd Wright and the Meaning of Material" Patterson, 1994, page 128, 130, 139, 145, 147, 226. "Frank Lloyd Wright" Thomson, 1997, page 146-147. "The Life & Works of Frank Lloyd Wright" Costantino, 1998, page 163, 169. "Frank Lloyd Wright - A Visual Encyclopedia" Thomson, 1999, page 190-191. "The Vision of Frank Lloyd Wright" Heinz, 2000, page 248, 251. "Frank Lloyd Wright Field Guide" Clayton, 2002, page 290-291, 468. "Frank Lloyd Wright American Master", Weintraub; Smith, 2009, pages 328-329. "Frank Lloyd Wright, Complete Works 1943-1959", Pfeiffer; Gossel, 2009, pages 406-407.

"Journal of the Taliesin Fellows" Komanecky, 1992, page 4-13. "The Wright neighborhood" Donelan & Forester, 2005. "My Story of Building Dr. Kalil’s House in Manchester, NH", Beaudoin & Martineau, 2007. Additional Wright Studies

SEE ADDITIONAL WRIGHT STUDIES Frank Lloyd Wright's First Published Article (1898) Photographic Chronology of Frank Lloyd Wright Portraits Frank Lloyd Wright's Nakoma Clubhouse & Sculptures."

A comprehensive study of Wright’s Nakoma Clubhouse

and the Nakoma and Nakomis Sculptures. Now Available.

Limited Edition. More information.Text copyright Douglas M. Steiner, Copyright 2014, 2020.