|

|

-

Wright Studies

Usonian Automatic Homes |

|

|

In 1936, Wright

developed a series of homes he called Usonian. They were

designed to control costs. Wright's Usonian houses had no

attics, no basements, and little ornamentation. He continued

to develop the concept, and in the early 1950s he first used

the term Usonian Automatic to describe a Usonian style house

made of inexpensive concrete blocks. The modular blocks

could be assembled in a variety of ways. Wright hoped that

home buyers could save money by building their own Usonian

Automatic houses. But assembling the modular parts proved

complicated, and most hired contractors to built their

Usonian houses. A precursor to the Usonian Automatic

system were the four Textile Block homes in California,

Millard (La Miniatura) S.214, Storer S.215, Freeman S.216,

and the Ennis S.217.

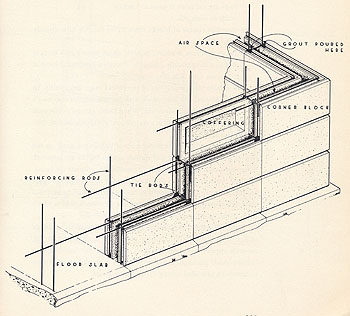

The basic concrete block of the Usonian

Automatic system is 12 x 24 inches. The blocks were laid

without mortar, with rebar placed both horizontally and

vertically in semicircular joints. After one or two rows of

blocks were laid, cement grout was pumped or poured into the

joints to bond the structure together. There were many homes

designed (projects), but only seven Usonian Automatic homes

were built using concrete molded blocks. The concept was

designed on a two foot grid floor plan. The walls were built

with 1' x 2' blocks and the ceiling blocks were 2' x 2'.

Others Usonian homes were built, but constructed of standard

concrete blocks and other material. May 2009. |

| |

Bock Ateliers

Pre-Usonian

Usonian Concrete

Block House (1934)

Usonian Automatic Homes

Completed Usonian Automatic Homes

Usonian Automatic Unbuilt Projects

In The Realm of Ideas 1988-1991

Concrete Construction Magazine

New York Times

Related Items

Seattle P-I

Related Reading |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

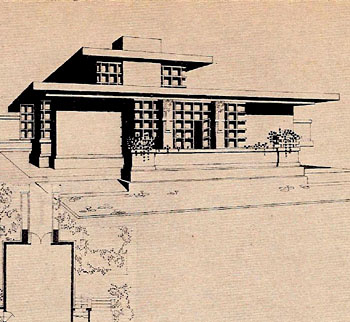

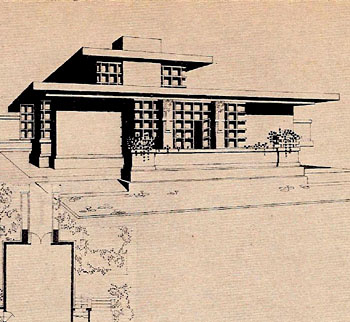

"Modern Architecture, Being the Kahn Lectures for

1930", Wright, 1931.

Of interest is the illustration that

proceeds Chapter 5. The illustration is entitled "Bock Ateliers.

Concrete. Slab Roof. Stone Washes and Water Table. Windows

Wrapping Corners to Express Interior Space. 1902." Bock met

Wright in 1892 while working for Adler & Sullivan. Bock’s first

commission from Wright was for the Frieze on the third floor of

the Heller Home (1896 - S.038). He also worked on other Wright

projects including the

Stork (1898) and

Boulder

(1898) for Wright’s own Studio, the

Dana Residence

(1902 - S.072),

Larkin Building (1903 - S.093),

Scoville Park

Fountain (1903 - S.094),

Unity

Temple (1904 - S.096),

Martin (1904 - S.100),

City National Bank

(1909 - S.155), and

Midway Gardens (1913 - S.180) just to name a few. In 1902 Wright to design a

home and studio for Bock. It was designed in

concrete. This was two years before the concrete Unity Temple,

twenty-one years before Wright’s first concrete block home, the

Millard Residence (1923 - S.214), and 49 years before the first

Usonian Automatic,

the Adelman Residence (1951 - S.344). Wright included the

concrete "Bock Ateliers" in his 1910

Wasmuth Portfolio Plate LXII. Although the 1902 window

casements were most likely designed in wood, Wright slightly

modified the 1931 window design to include mitered glass

corners, a precursor to Wright’s 1951 Usonian Automatic Homes. "Modern Architecture, Being the Kahn Lectures for

1930", Wright, 1931.

Of interest is the illustration that

proceeds Chapter 5. The illustration is entitled "Bock Ateliers.

Concrete. Slab Roof. Stone Washes and Water Table. Windows

Wrapping Corners to Express Interior Space. 1902." Bock met

Wright in 1892 while working for Adler & Sullivan. Bock’s first

commission from Wright was for the Frieze on the third floor of

the Heller Home (1896 - S.038). He also worked on other Wright

projects including the

Stork (1898) and

Boulder

(1898) for Wright’s own Studio, the

Dana Residence

(1902 - S.072),

Larkin Building (1903 - S.093),

Scoville Park

Fountain (1903 - S.094),

Unity

Temple (1904 - S.096),

Martin (1904 - S.100),

City National Bank

(1909 - S.155), and

Midway Gardens (1913 - S.180) just to name a few. In 1902 Wright to design a

home and studio for Bock. It was designed in

concrete. This was two years before the concrete Unity Temple,

twenty-one years before Wright’s first concrete block home, the

Millard Residence (1923 - S.214), and 49 years before the first

Usonian Automatic,

the Adelman Residence (1951 - S.344). Wright included the

concrete "Bock Ateliers" in his 1910

Wasmuth Portfolio Plate LXII. Although the 1902 window

casements were most likely designed in wood, Wright slightly

modified the 1931 window design to include mitered glass

corners, a precursor to Wright’s 1951 Usonian Automatic Homes. |

| |

|

|

|

Detail of "Bock Ateliers" 1931 Modern Architecture. |

| |

|

|

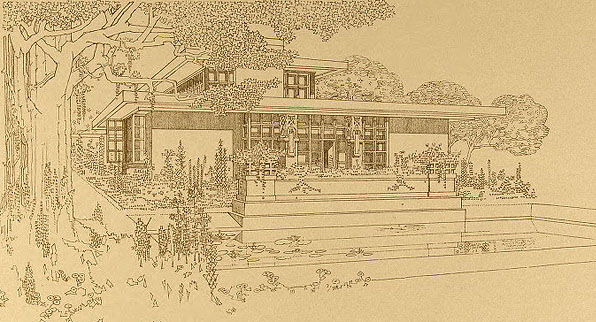

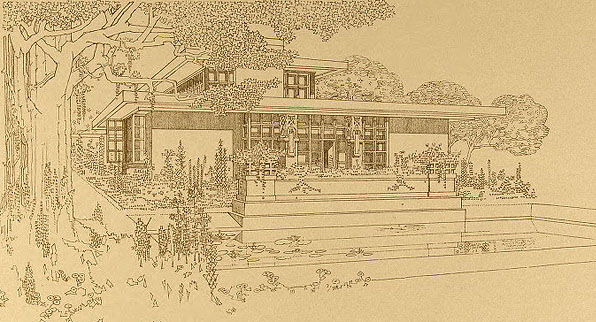

| Detail of "Bock

Ateliers" 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio Plate LXII. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

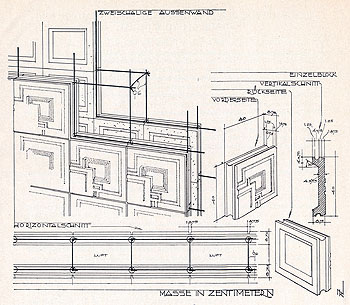

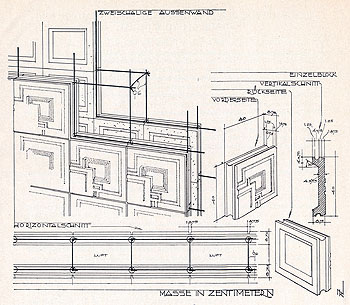

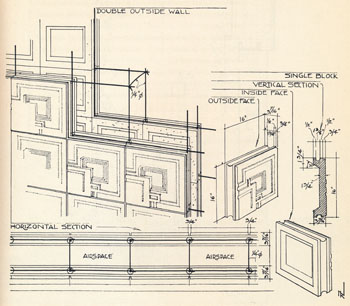

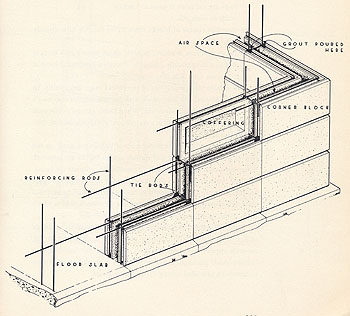

Date:

1926

Title:

Charles Ennis Residence, Los Angeles, CA,

Illustration 1926 (1923 - S.217).

Description:

Diagram of

the cement block construction for the Ennis House. Illustration

published in

Frank Lloyd

Wright: Aus dem Lebenswerke eines Architekten, De Fries,

1926, p.63. Caption: "Darstellung der Zementblockbauweise des

Architekten Frank Lloyd Wright. Masse in zentimetern."

(Representation of the cement block construction by the

architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Dimensions in centimeters.) In

1921 Frank Lloyd Wright prepared a "Study for Block House in

Textile Block Construction,"

Frank Lloyd Wright

Monograph 1914 - 1923, Pfeiffer, 1990, p.204-205.

According to Sweeney, Wright attempted to obtain a patent for

the system in 1921,

Wright

in Hollywood, 1994, p.43-44. A blueprint was prepared of

this drawing in German for De Fries, and is published in

Frank Lloyd Wright

Monograph 1914 - 1923, Pfeiffer, 1990, p.242. The

blueprint is also published in

Wright 1917-1942, Pfeiffer, 2010, p.90. This

concept was used for

Usonian Automatic Homes.

Size:

Copy 9.25 x 8 B&W photograph.

S#:

0172.55.0721 |

|

|

|

|

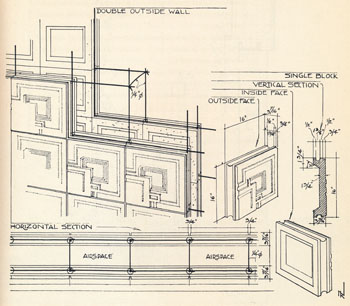

Date:

1926/1954

Title:

Charles Ennis

Residence, Los Angeles, CA, Illustration 1954 (1923 - S.217).

Description:

Diagram of the

cement block construction for the Ennis House. Illustration

published in

The Natural House,

Wright, 1954, p.203. This illustration was first published in

German in

Frank Lloyd Wright: Aus dem

Lebenswerke eines Architekten, De Fries, 1926, p.63. Caption:

"Representation of the cement block construction by the

architect Frank Lloyd Wright." In 1921 Frank Lloyd Wright

prepared a "Study for Block House in Textile Block

Construction," Frank

Lloyd Wright Monograph 1914 - 1923., Pfeiffer, 1990, p.204-205.

According to Sweeney, Wright attempted to obtain a patent for

the system in 1921, Wright in Hollywood,

1994, p.43-44. A blueprint was prepared of this drawing in

German for De Fries, and is published in Frank

Lloyd Wright Monograph 1914 - 1923., Pfeiffer, 1990, p.242. The

blueprint is also published in

Wright 1917-1942, Pfeiffer, 2010, p.90.

Size:

Copy 9.25 x 8 B&W

photograph.

S#:

0992.10.0721 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

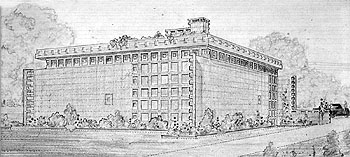

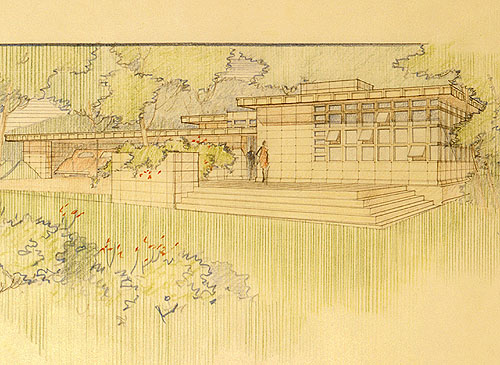

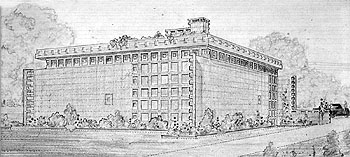

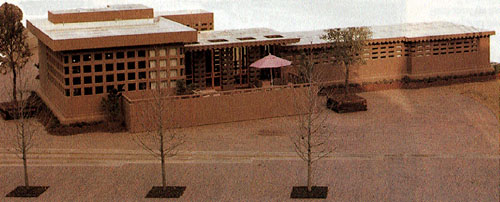

Date:

1934

Title:

Broadacre City, Usonian Concrete Block

House, Perspective, Circa 1934.

Description:

Perspective view of the Usonian Concrete Block House designed by

Frank Lloyd Wright. Published in The Living City,

Wright, 1958, p.70. Text on sleeve: "Wright, F. L. - Broadacre City

- Usonian House . 3-1. Usonian Concrete Block House Project.

Render., Perspective drawing. 1924-29. Broadacre City Project.

Wright, Frank Lloyd. U of Virginia FAIC." Acquired from the archives

of the University of Virginia.

Size:

35mm Color slide, sandwiched between glass, plastic mount.

S#:

0376.07.0420 |

|

|

|

|

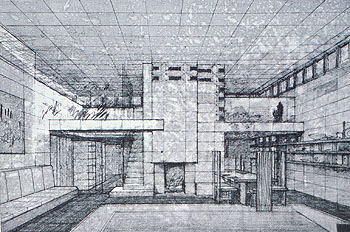

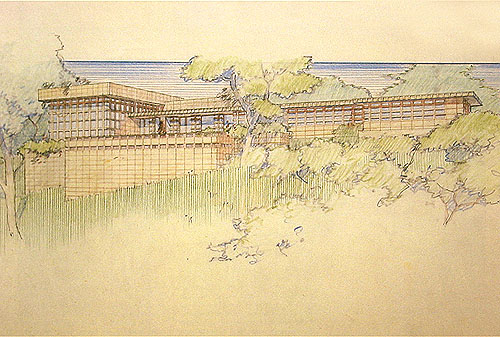

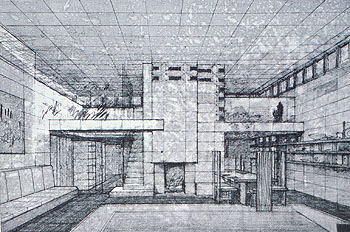

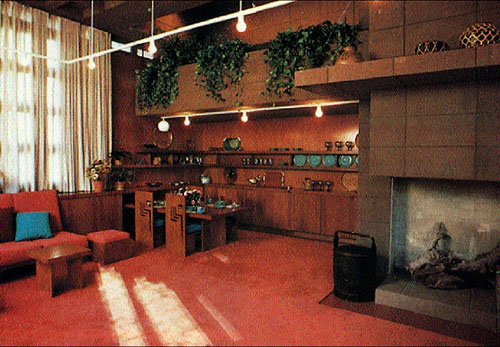

Date:

1934

Title:

Broadacre City, Usonian Concrete Block

House, Living Room Perspective, Circa 1934.

Description:

Perspective view of the Usonian Concrete Block House Living Room

designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Published in The Living City,

Wright, 1958, p.70. Text on sleeve: "Wright, F. L. - Broadacre City

- Usonian House . 3-2. Usonian Concrete Block House Project.

Render., Interior Living Room perspective drawing. 1924-29.

Broadacre City Project. Wright, Frank Lloyd. U of Virginia FAIC."

Acquired from the archives of the University of Virginia.

Size:

35mm Color slide, sandwiched between glass, plastic mount.

S#:

0376.08.0420 |

|

|

|

|

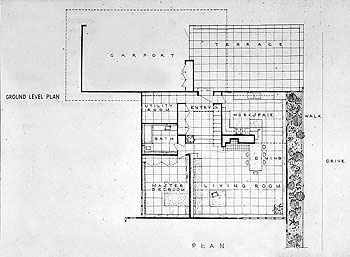

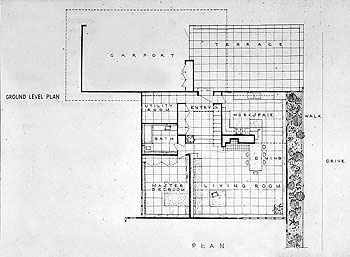

Date:

1934

Title:

Broadacre City, Usonian Concrete Block

House, Ground Plan, Circa 1934.

Description: Ground

Plan for the Usonian Concrete Block House designed by Frank Lloyd

Wright. Published in The Living City,

Wright, 1958, p.71. Text on sleeve: "Wright, F. L. - Broadacre City

- Usonian House . 1-1. Usonian Concrete Block House Project. Plan

Ground Floor. 1924-29. Broadacre City Project. Wright, Frank Lloyd.

U of Virginia FAIC." Acquired from the archives of the University of

Virginia.

Size:

35mm Color slide, sandwiched between glass, plastic mount.

S#:

0376.09.0420 |

|

|

|

|

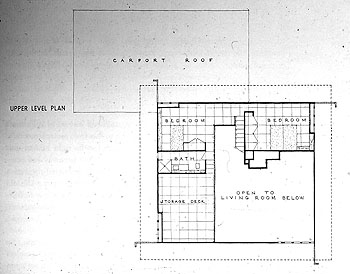

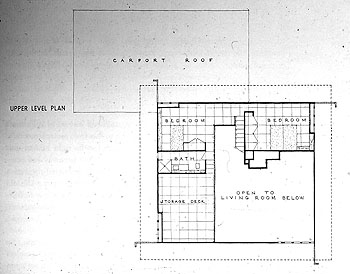

Date:

1934

Title:

Broadacre City, Usonian Concrete Block

House, Upper Level Plan, Circa 1934.

Description: Upper

Level Plan for the Usonian Concrete Block House designed by Frank

Lloyd Wright. Published in The Living City,

Wright, 1958, p.71. Text on sleeve: "Wright, F. L. - Broadacre City

- Usonian House . 1-1. Usonian Concrete Block House Project. Plan

Upper Level. 1924-29. Broadacre City Project. Wright, Frank Lloyd. U

of Virginia FAIC." Acquired from the archives of the University of

Virginia.

Size:

35mm Color slide, sandwiched between glass, plastic mount.

S#:

0376.10.0420 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

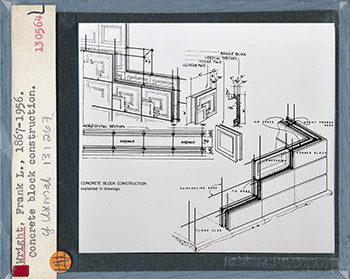

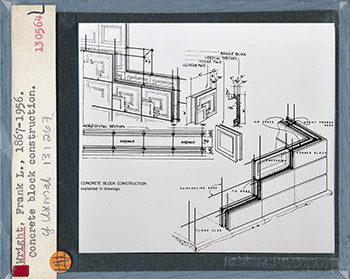

Date:

1926/1954

Title:

Vintage 4" x 3.25" Magic Lantern Slide of

Concrete Block Construction 1926 / 1954.

Description:

Copy photograph of

a combination to two illustrations. The top left is an

illustration of the construction of the Charles Ennis Residence,

Los Angeles, CA, Illustration (1923 - S.217). It was published

in German in

Frank Lloyd Wright: Aus dem

Lebenswerke eines Architekten, De Fries,

1926, p.63. It was published in English in The Natural House,

Wright, 1954, p.203.

The

lower right is the Usonian Automatic

House Construction (S#0992.11) Illustration, 1954. Diagram

of the concrete block construction for the Usonian Automatic

House. Illustration was published in

The Natural House,

Wright, 1954, p.201.

Magic lantern slides were used in the U.S. during the late 1800s

through the first half of the 1900s. Text: “Sectional View of

the Dining Room. Sectional View of the Living Room. Sectional

View of Entry.”

Text on

face of slide: “Wright, Frank L., 1867-1956 (sic).concrete block

construction. 130564. Art Dept Smith College.” Acquired from the

Art Department at Smith College.

Size:

Magic lantern slide

4" x 3.25", Transparency: 3" x 2.6"

S#:

0172.61.0725

Left: Detail of Magic Lantern Slide Above. |

|

|

|

|

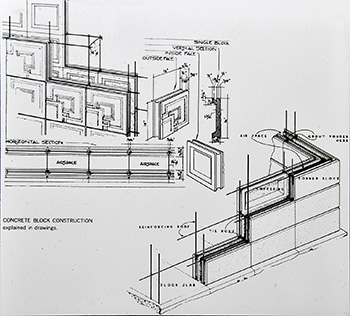

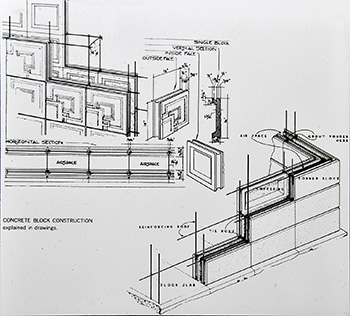

Date:

1954

Title:

Usonian Automatic House Construction

Illustration 1954.

Description:

Diagram of the concrete block construction

for the Usonian Automatic House. Illustration published in

The Natural House,

Wright, 1954, p.201. In 1921 Frank Lloyd Wright prepared a "Study

for Block House in Textile Block Construction," Frank

Lloyd Wright Monograph 1914 - 1923., Pfeiffer, 1990, p.204-205.

According to Sweeney, Wright attempted to obtain a patent for the

system in 1921, Wright in Hollywood,

1994, p.43-44. In 1923, Frank Lloyd Wright designed four textile

block homes in Los Angeles. 1) Millard (La Miniatura) (1923 -

S.214); 2) Storer (1923 - S.215); 3) Freeman (1923 - S.216); 4)

Ennis (1923 - S.217). Circa 1934, Wright designed a Usonian Concrete

Block House for Broadacre City. In 1936, Wright developed a series

of homes he called Usonian. They were designed to control costs.

Wright's Usonian houses had no attics, no basements, and little

ornamentation. He continued to develop the concept, and in the early

1950s he first used the term Usonian Automatic to describe a Usonian

style house made of inexpensive concrete blocks. The modular blocks

could be assembled in a variety of ways. Wright hoped that home

buyers could save money by building their own Usonian Automatic

houses. But assembling the modular parts proved complicated, and

most hired contractors to built their Usonian houses. A precursor to

the Usonian Automatic system were the four Textile Block homes in

California. The basic concrete block of the Usonian Automatic system

is 12 x 24 inches. The blocks were laid without mortar, with rebar

placed both horizontally and vertically in semicircular joints.

After one or two rows of blocks were laid, cement grout was pumped

or poured into the joints to bond the structure together.

Size:

8.75 x 8 B&W copy photograph.

S#:

0992.11.0721 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Completed

Usonian Automatic Homes |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Tracy (1955 - S.389) |

|

|

Copyright

Douglas M. Steiner, 2001.

(Tracy Study) |

|

|

| |

|

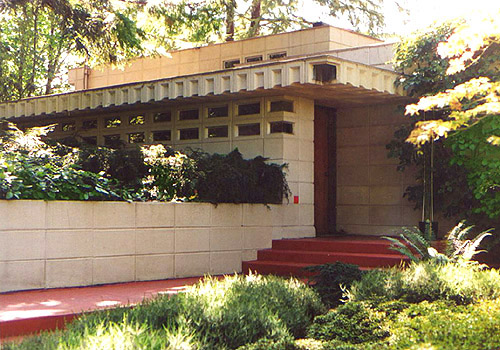

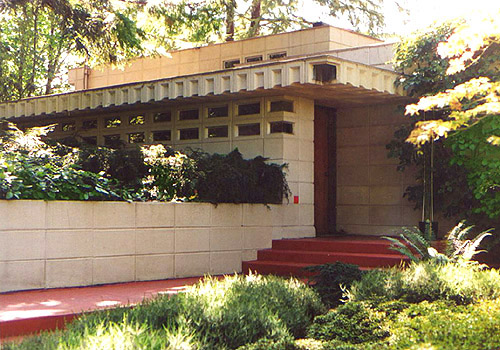

Pappas (1955 - S.392) |

|

|

Courtesy of

ocad123 Flickr,

2002. |

| |

|

|

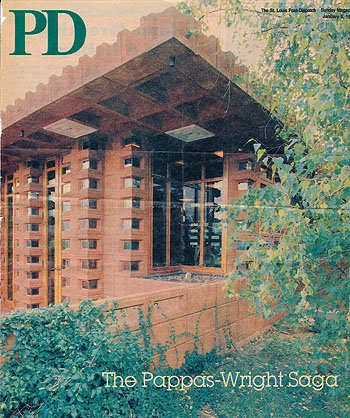

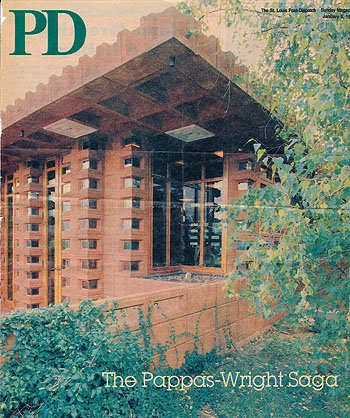

Date:

1986

Title:

St. Louis Post-Dispatch - January 5, 1986 (Published by the

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis) (Article only)

Author:

Porter, E.F. Jr.; Photos: Holt, Robert C. Jr.

Description:

"The Saga of Ted & Bette Pappas & Frank Lloyd Wright. If you

are rich and famous – or even merely rich – a designer house

is like a designer garment: you can enjoy the satisfaction

of ownership without the agonies of creation and upkeep, and

you can get out of it whenever you feel like it. But suppose

you're like Theodore and Betty Pappas, by their own account

just ordinary folk: struggling and hard-working when they

were young, and now, in their late-middle years, comfortable

but not wealthy West County empty-nesters, with four grown

children and several grandchildren... Supposed to most

extraordinary thing about you is a steely resolve to live in

a house designed for you by the world’s most famous

architect. Suppose that house must serve, not just as part

of a collection of pied-a-terra (Condos in the Caribbean,

A-frames in Aspen), but home..." Includes 6 photographs.

Size:

10 x 11.5

Pages:

Pp Cover, 5-10

ST#:

1986.92.0717 |

|

|

|

|

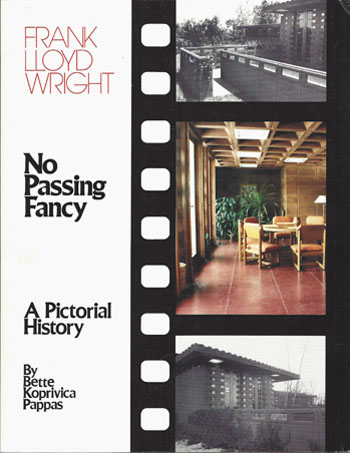

Date:

1995

Title:

Frank Lloyd Wright: No Passing Fancy. A Pictorial History

(Soft Cover) (Published by Betty K. Pppas, St. Louis,

Missouri)

Author: Pappas, Bette Koprivica

Description:

Theodore and Bette Pappas Residence.

Preface: For the last thirty years people have asked my

husband and me how we came to choose Frank Lloyd Wright as

our architect. Did we get to meet him personally? Was he

very expensive? What was it like living in a home designed

by him? Once, a woman came up to us at a dinner party, after

learning Mr. Wright had designed a home for us, and asked is

she could touch us. During our twenty years of occupancy,

from 1964 to 1984, we have given guided tours and first-hand

information to students and faculty members from community

colleges, Washington University, University of Missouri-St.

Louis, and Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville.

Unfortunately, we weren’t able to accommodate all requests

for tours and information. Still unanswered is a small stack

of letters and questionnaires requesting in formation on how

we view the house - for instance, do we view the wall as a

wall, windows, or screens, etc. Since detailed

questionnaires like these are so time-consuming, we couldn’t

answer them individually... (Second edition)

(See Pappas furniture.)

Size:

8.5 x 11

Pages: Pp 57

ST#:

1995.89.0517 |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

Usonian Automatic Unbuilt Projects |

|

|

|

In The Realm of Ideas: Usonian Automatic Traveling

Exhibit - 1988-1991 |

|

|

|

From January 1988 through March

1991, "Frank Lloyd Wright:

In The Realm of Ideas" a traveling exhibition included

a full-scale Usonian Automatic model. The design that was

chosen for the full-scale model was the

Sussman Residence (project). The full-scale home used

lightweight construction material replicating concrete. This

enabled quick dismantling, transporting and re-erection of

the model. The tour exhibited in

eight cities. Dallas (Jan-Apr 1988), Washington DC

(June-Sept 1988), Miami (Dec-Feb 1989), Chicago (Jun-Sept

1989), Bellevue, WA (Oct-Jan 1990), San Rafael, CA (Feb-May

1990), San Diego (Jun-Sept 1990) and Scottsdale (Dec-Mar

1991). |

| |

| Dallas

(January - April 1988) |

|

|

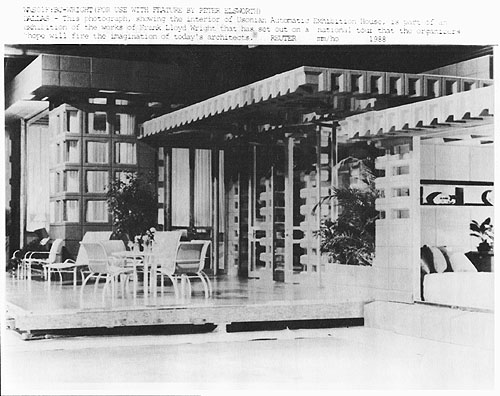

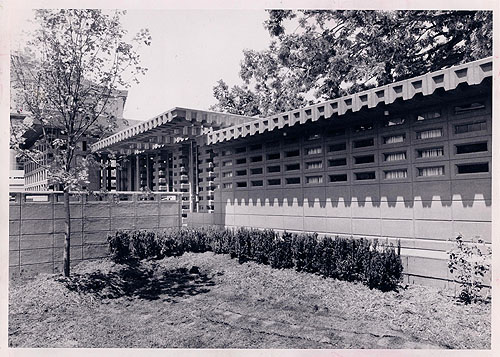

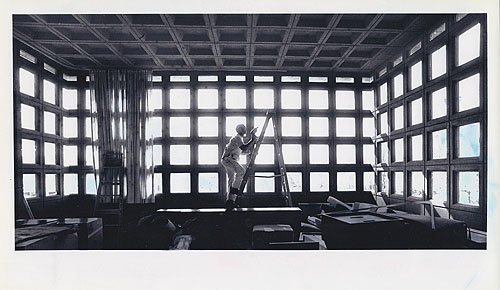

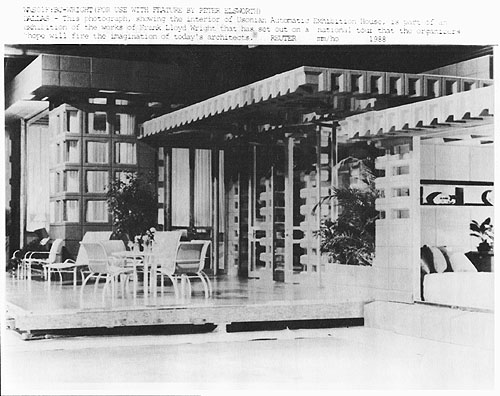

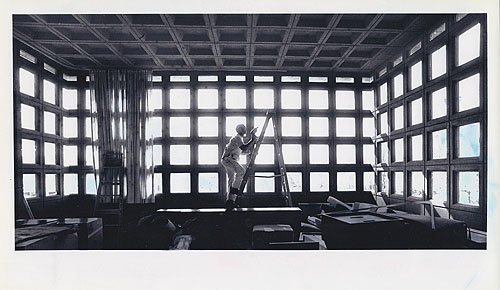

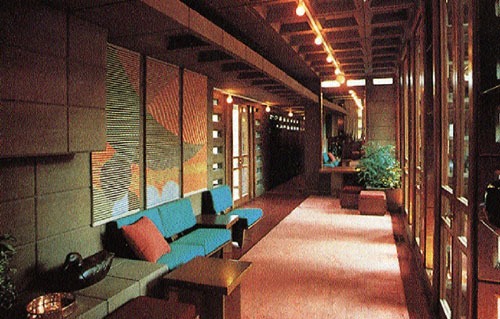

Usonian Automatic

Traveling Exhibit House. Dallas (January-April, 1988). Caption on face:

"Dallas – This photograph, showing the interior of Usonian Automatic

Exhibition House, is part of an exhibition of the works of Frank Lloyd Wright

that has set out on a national tour that the organizers hope will fire the

imagination of today’s architects. Reuter. 1988." Stamped on verso: "Feb 12

88". The full size Usonian Automatic model home was exhibited in eight

cities. Dallas (Jan-Apr 1988), Washington DC (June-Sept

1988), Miami (Dec-Feb 1989), Chicago (Jun-Sept 1989),

Bellevue, WA (Oct-Jan 1990), San Rafael, CA (Feb-May 1990),

San Diego (Jun-Sept 1990) and Scottsdale (Dec-Mar 1991).

Acquired from the archived of the Chicago Tribune. See more information on

the Usonian

Automatic Traveling Exhibition. |

| |

| Dallas

(January - April 1988) |

|

|

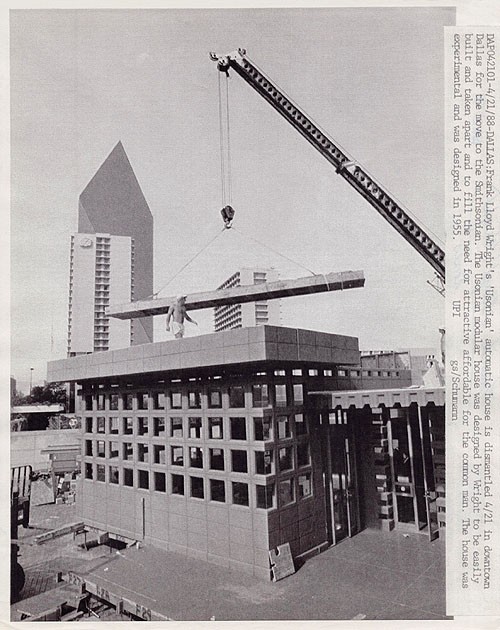

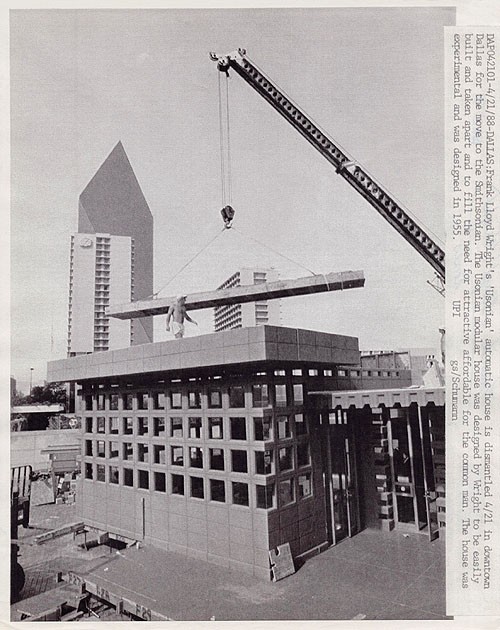

Usonian Automatic

Traveling Exhibit House. Dallas (January-April, 1988). Caption on face:

"Dallas – Frank Lloyd Wright’s ‘Usonian’ automatic house is

dismantled 4/21 in downtown Dallas for the move to the

Smithsonian. The Usonian modular

house was designed by Wright to be easily built and taken apart and to fill

the need for attractive affordable for the common man. The house was

experimental and was designed in 1955. UPI." Stamped on verso: "Apr 25 88".

The full size Usonian Automatic model home was exhibited in eight cities.

Dallas (Jan-Apr 1988), Washington DC (June-Sept 1988), Miami

(Dec-Feb 1989), Chicago (Jun-Sept 1989), Bellevue, WA

(Oct-Jan 1990), San Rafael, CA (Feb-May 1990), San Diego

(Jun-Sept 1990) and Scottsdale (Dec-Mar 1991). Acquired from

the archived of the Chicago Tribune. See more information on

the Usonian

Automatic Traveling Exhibition. |

| |

| Chicago

(June - September 1989) |

|

|

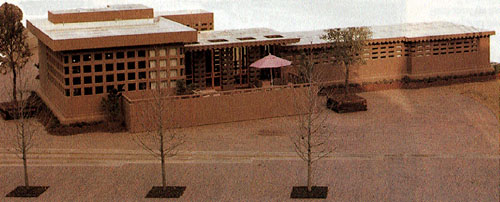

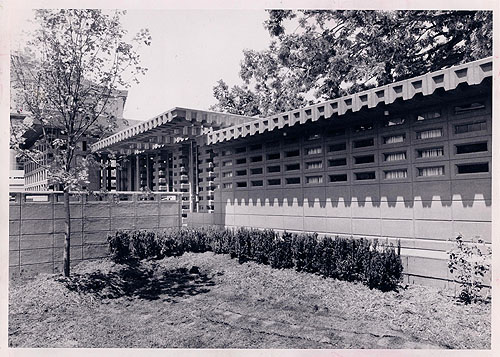

Usonian Automatic Traveling Exhibit

House. Chicago. The

Chicago Exhibit was held from June - September 1989 at the Museum of Science

and Industry. See more information on

the Usonian

Automatic Traveling Exhibition. |

| |

| Bellevue,

WA (October - January 1990) |

|

|

Usonian Automatic Traveling Exhibit

House. Seattle. The

Seattle Exhibit was held from October - January 1990 at the

Bellevue Art Museum. See more information on

the Usonian

Automatic Traveling Exhibition. |

| |

| San

Rafael, CA (February - May 1990) |

|

|

Marin County Civic Center,

San Rafael, CA

(Feb-May 1990), Copyright

SDR Design 1990. |

| |

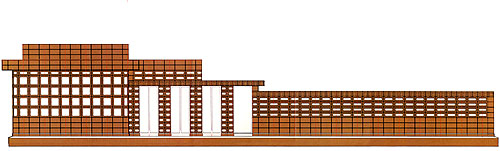

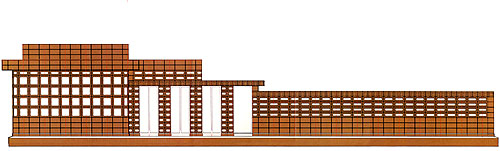

| Floor Plan |

|

| Floor plan

for the Usonian Automatic Traveling Exhibit and the Sussman

Residence. |

| |

| Side View |

|

| Side view

for the Usonian Automatic Traveling Exhibit and the Sussman

Residence. |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

Concrete Construction Magazine |

| |

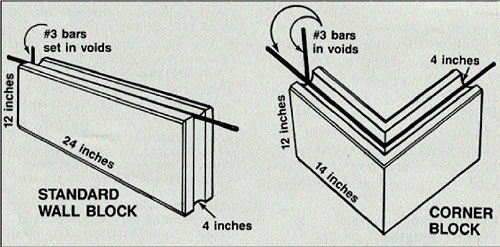

Usonian Automatic:

Wright's Concrete Masonry

Copyright The Aberdeen Group, 1988

Published in Copcrete Construction Magazine, November 1, 1988

By Mary K. Hurd |

|

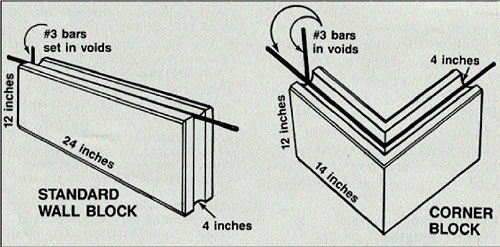

Abstract:

About 1950, Frank Lloyd Wright designed

a concrete masonry building system that he called Usonian Automatic.

Automatic was used to suggest that the owner might participate in

the actual construction of the home, laying or even making the

blocks. Beginning in 1951 a number of these houses were constructed

across the nation from California to New Hampshire. The basic

concrete block of the Usonian Automatic system is 4x12x24 inches.

The blocks are laid up without mortar, with #3 reinforcing bars

placed both horizontally and vertically in semicircular voids in the

contacting faces. After one or two courses of blocks are laid, grout

is pumped or poured into the voids to embed the bars and bond the

structure together. |

|

|

|

Click to see full PDF article. |

| |

|

|

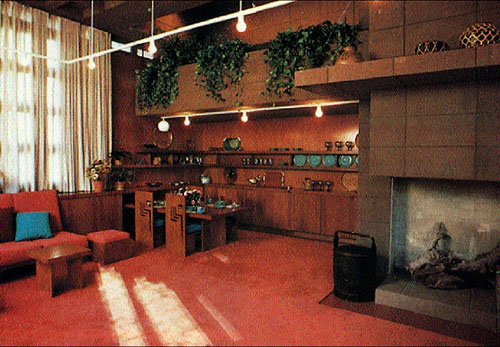

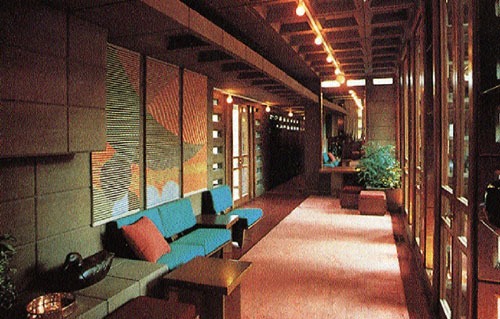

Usonian Automatic

home now touring the United States was designed in 1955 by Frank

Lloyd Wright. For ease in setting up and shipping, concrete masonry

was realistically simulated in the 1,800-square-foot exhibit house.

Copyright The Aberdeen Group, 1988. |

| |

|

|

Standard Usonian

blocks make up the fireplace wall of the exhibit home. Dining area

on the left displays Wright-designed furnishings. Copyright The Aberdeen Group, 1988. |

| |

|

|

Interior view of

the exhibit home shows deeply coffered concrete masonry ceiling.

Window wall at the right is made up of concrete block units inset

with glass. Note exposed standard Usonian Automatic blocks in the

wall at the left. Copyright The Aberdeen Group, 1988. |

| |

|

| The basic Usonian

Automatic block has a semicircular groove running around the entire

block on its narrow face. Blocks are laid without mortar, but with

reinforcing bars in the grooves, both horizontally and vertically.

Grout poured or pumped into the cavities surrounds the rebar and

unifies the construction.

Copyright The Aberdeen Group, 1988. |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

New York

Times |

| |

(Note, due to the fact that the

internet is constantly changing, and items that

are posted change, I have copied excerpts of the text, but give all the

credits available.) |

| |

|

Wright Seen Anew as an Architect of Thoughts

By Paul Goldberger

The New York Times, February 7, 1988

http://www.nytimes.com/1988/02/07/arts/architecture-view-wright-seen-anew-as-an-architect-of-thoughts.html?sec=&spon=&pagewanted=1

In the 28 years since Frank Lloyd Wright's death,

his associates, who have tried to keep the flame of his reputation

burning, have often done more to damage his name than to enhance it.

Under the rubric of Taliesin Associated Architects (named for the

architect's famous houses in Spring Green, Wis., and Scottsdale,

Ariz.) they have produced new buildings that are generally mediocre

imitations of the great architect's late work. Through their Frank

Lloyd Wright Foundation, they have continued Wright's practice of

inviting students to pay for the privilege of studying with the

master, even though there is no longer a master. And they have sold

off various original Wright drawings to keep their operation going.

It has all too often

felt like a cult more than a living enterprise. Given all of this,

expectations had not been particularly high for the latest project

the Wright disciples have undertaken, a major exhibition intended to

travel the country and serve as an introduction to Wright's ideas.

Focusing on ''ideas'' more than actual buildings seemed as if it

would, if anything, encourage the tendency to view Wright in

quasi-religious, instead of realistic, terms: Wright the deity, not

Wright the architect.

But the pleasant

surprise of the large and striking exhibition ''Frank Lloyd Wright

in the Realm of Ideas'' that opened last month at the Dallas Museum

of Art and the adjoining Trammell Crow Center Pavilion, is that it

holds deification to a minimum. This is hardly a critical

exhibition; those interested in a dissenting view on Frank Lloyd

Wright must look elsewhere. But it is perhaps the most inviting and

articulate introduction to Wright's basic ideas that anyone has

offered the public in many years. The exhibition is lively and

handsome; it includes a wide range of models, original furniture

pieces, blown-up reproductions of Wright drawings and spectacular

color photographs enlarged to mural size. The climax is a full-scale

version of one of Wright's Usonian houses that has been erected on

the grounds of the Dallas Museum of Art, with the unlikely

background of the city's downtown office towers.

Let there be no mistake:

this is not the major retrospective of Wright that has been awaited

for many years, and neither is it an exhibition that will advance

the frontiers of Wright scholarship. It is a layman's show, not a

scholar's. But it presents Wright in a manner that is clear and

straightforward, and that should do much to excite the public's

interest in the man who was unquestionably America's greatest

architect of this century. And it does so without pandering to the

public or grossly oversimplifying Wright's ideas.

The exhibition, which

was organized by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in cooperation

with the Scottsdale Arts Center Association and underwritten by the

Whirlpool Corporation and the Kohler Company, has been organized in

an unusual way. It is not chronological, or arranged by building

type. Rather, the curators, Gerald Nordland, an art historian, and

Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, the chief archivist at the Frank Lloyd Wright

Foundation, have classified the material into four thematic

sections: ''The Destruction of the Box,'' ''The Nature of the

Site,'' ''Materials and Methods'' and ''Building for Democracy,''

echoing themes that were central to Wright's own concerns, and that

the architect returned to again and again in his own writings. It is

Wright himself who speaks throughout this exhibition: the pleasing

thing is that the curators have been discreet, and have placed

themselves in the background. Only Wright's own words are used as

the wall text for the exhibition; in every way is this show Wright

on Wright. This is vastly more convincing than being presented with

testaments to Wright from his disciples. For the architect himself,

though he tended toward wild exaggeration and on occasion simplified

or revised facts to suit his own ends, had a glorious rhetorical

flourish. It is actually rather ironic, given how desperately

Wright's followers have tried over the years to maintain his

reputation, that they have done it best by doing the simplest thing

- putting themselves in the background and letting Wright in effect

present himself to us.

The thematic organization means that some important

Wright buildings, such as Fallingwater, the great house of 1937 in

Mill Run, Pa., or the Johnson Wax Company headquarters in Racine,

Wis., also of 1937, pop up again and again in the exhibition. But

this only helps to underscore the continuity of these themes

throughout the architect's career, and the fact that his important

work transcended narrow categorization within a single theme. The

spectacular cantilevered structure of Fallingwater, for example, was

as critical an example of Wright's desire to create forms that

opened up the traditional box as it was indicative of his ability to

respond subtly and powerfully to the particular nature of a dramatic

site.

These first two themes -

breaking out of the box and working with nature - actually work best

in this format, since they are the easiest to explain. It is not

hard to trace Wright's struggle to break out of the box from his

early Prairie houses with their flowing horizontal space to such

late works as the great spiral rotunda of the Guggenheim Museum. (An

early model of the Guggenheim forms the centerpiece of this

section.) And it is pleasing, even moving, to be taken through these

buildings with Wright's own words as our only text, telling us, as

in the words placed beside a picture of his great Unity Temple of

1906, that ''there perhaps is where you will find the first real

expression of the idea that the space within the building is the

reality of the building. . .When I finished Unity Temple, I had it.

I knew I had the beginning of a great thing, of a great truth in

architecture.''

So, too, with the

section on the relationship of buildings to nature: these short

snatches of Wright's words, flush with hyperbole though they be,

become an almost endearing accompaniment to dramatic photographs.

''A house, we like to believe, can be a noble consort to man and the

trees'' is the beginning of the text panel before a picture of the

Pew House, in Shorewood Hills, Wis., a structure of wood set within

a lush landscape. But the other sections are less convincing.

''Materials and Methods'' calls for more rigorous analysis than it

gets here, and is something of a catchall for numerous interesting

projects, such as Wright's unbuilt skyscraper for The San Francisco

Call of 1912, that did not fit elsewhere. As for ''Building for

Democracy,'' this was always the vaguest and most overblown sphere

of Wright's rhetoric, and it is still vague here, even though this

section does have its share of excellent illustrative material and

the same splendid verbal accompaniment of the other sections.

And that brings us to

the real crowd-pleaser in this exhibition, the Usonian Automatic

House. Wright called many of his smaller houses, intended to bring

architecture to the masses, Usonian; this particular one was

designed in 1955, and was to have been built in concrete block,

called ''automatic'' because Wright wanted the building system to be

simple enough to avoid the cost of skilled labor. (This version has

been built in synthetic material to simulate the appearance of

concrete block to make assembly, dismantling and moving easier.) If

you can get over your surprise at the presence of a microwave and

other post-Frank Lloyd Wright appliances that were obviously the

price of Whirlpool and Kohler's sponsorship, a walk through the

house is a marvelous moment. It is not large - just 1,800 square

feet - but Wright's ability to control and manipulate space and

light was so remarkable that the house feels significantly bigger.

The ceiling plane begins at 9 1/2 feet at the entrance, goes down to

7 1/2 feet in the bedrooms, and leaps up to 12 1/2 feet in the

living room, and there is real spatial drama to this movement.

Wright really did care about bringing architecture to everyone. This

at once separates him from most of the architects practicing today

and enobles him, and it is the earnestness of that desire that is

the real message ''Frank Lloyd Wright in the Realm of Ideas'' leaves

us with.

The show will be on view

in Dallas until April 17, after which it will embark on a national

tour through 1990. |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

The

Usonian Automatic Traveling Exhibit: In The Realm of Ideas |

| |

|

|

| Books, Brochures,

PR, Articles |

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

Seattle Post-Intelligencer |

| |

(Note, due to the fact that the

internet is constantly changing, and items that

are posted change, I have copied excerpts of the text, but give all the

credits available.) |

| |

|

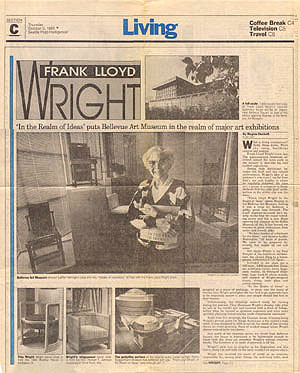

FRANK

LLOYD WRIGHT 'IN THE REALM OF IDEAS' PUTS BELLEVUE ART MUSEUM IN THE

REALM OF MAJOR ART EXHIBITIONS FRANK

LLOYD WRIGHT 'IN THE REALM OF IDEAS' PUTS BELLEVUE ART MUSEUM IN THE

REALM OF MAJOR ART EXHIBITIONS

By

Regina Hackett

Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 5, 1989

What is living architecture? Betty Boop knew. When

she sang, buildings swayed and danced.

Frank Lloyd Wright knew, too. The quintessential

American architect coined the term early in the century to describe

his own exalted aspirations.

Seeing little distinction between the built and the

natural environment, Wright's idea of an architect's role wasn't too

far from God's, the only builder to whom he regularly deferred. He

once told a group of architects in Santa Barbara that the only good

architecture in the entire city was the trees.

"Frank Lloyd Wright: In the Realm of Ideas" opens

Monday at the Bellevue Art Museum. Getting it was a coup for

Bellevue, a giddy, great leap forward. The small museum-in-a-mall

isn't exactly in-the-loop for major traveling shows and this is one.

Since opening last January at the Dallas Museum of Art, it has

toured the country to great enthusiasm from critics and crowds

alike.

"We have hordes of volunteers for the show," said

director LaMar Harrington, "all kinds of guards. We have to be

prepared for crowds, but maybe no one will come."

Not likely. Wright is the Paul Bunyan of the

American architecture, the closest thing to a home-grown,

architectural cult figure.

Included in the show are a full-scale,

1,800-square-foot Usonian automatic house, seven large-scale models,

15 freehand drawings, huge back-lit photo murals, and clusters of

Wright-designed chairs, china, stain glass and eating utensils.

"In the Realm of Ideas" is designed as a piece of

pedagogy, to drum into the heads of viewers four Wright principles:

the box had to go, materials have to be respected, nature is great

and people should feel free in their houses.

Unfortunately, the drawings weren't ready for

viewing during the preview. They illuminate Wright's dreamy side,

what he saw in his mind's eye and covered with a flush of foliage,

before what he viewed as ignorant engineers and even more ignorant

planning bureaucracies made compromise necessary.

Aside from the drawings, the Usonian house (Usonian

being Wright's private name for things American) is the exhibit's

high point. It was designed in 1955 to satisfy the needs of

low-income clients or, more precisely, those of modest means whom

Wright always wanted to be his clients.

Just south of the museum across the street from

Bellevue Square, the house is fabricated to be lightweight enough to

travel with the show yet resemble Wright's precast concrete blocks.

The furniture in it, made of plywood, is all his.

Wright's style was as singular as his fingerprint,

and this house, slung low and wide on the land, couldn't be anyone

else's.

Wright has received his share of credit as an

inventor, responsible for, among other things, the wall-hung toilet,

steel office furniture, flexible joints for earthquake protection,

indirect lighting and plate glass commercial doors. He's famous for

breaking faith with the box, loving materials both high and low and

wanting to harmonize with, not dominate, the landscape.

Yet he's clearly the unsung hero of roller rinks, to

which his Usonian house seems related. Roller rinks use his kind of

space: low and lean, good for sprints and figure 8's, bad for high

jumps.

His style changed remarkably little over the course

of his long career, except that the exterior angles softened. He was

acutely aware that the new century would call for new styles, and he

wanted his to be a trump.

It was. After five years working as a draftsman in

Louis Sullivan's Chicago office, Wright set out on his own in 1893,

having absorbed crucial lessons from architects such as H.H.

Richardson and Sullivan, who were modernist pioneers advocating

rational principle amid the welter of late 19th century decoration.

His pool of sources was the widest of his generation. It included

Japanese teahouses and summer palaces, Hopi rock dwellings and

Venetian row houses on the water.

One can only imagine the surprise of those who came

upon his early houses. They jut out. They were new and still look

oddly new, a statement of faith in a rosy future of unlimited

resources and scientific breakthroughs.

As Narciso Menocal's excellent catalog essay points

out, Wright was deeply impressed by Edward Bellamy's "Looking

Backward," a novel published in 1888 that imagined American cities

of complete harmony by the year 2000.

Bellamy brought a top hat to socialism. He assumed

that everyone wanted understated elegance and good table manners,

and all people would participate in a collective, white Protestant

male ideal, if they only could.

Wright agreed and wanted to be the white Protestant

male in charge. If he built a house for you, he wanted you to be

free all right, free to live life completely bound by his style. He

chose or designed all the furniture and its placement, the plants,

both indoor and out, the rugs, the lighting and heating system. God

help anyone who even thought of adding any non-Wright touches to

"his" living quarters.

The original scale model for New York's Guggenheim

Museum is the best looking one in the show. Its puttylike, white

surface has softened with age and now looks like Claes Oldenburg

made it.

In person, however, the Guggenheim is absolute

Wright, the most distinctive museum in the world and the least

admired by painters and sculptors. Wright's great rampways coil down

through interior space and make the art in it an afterthought.

Someday there will be regular tours of Frank Lloyd

Wright houses across the country. Till then, seeing this exhibit is

the easiest way to appreciate both the master's range and his

foibles.

|

|

| |

|

|

Related

Reading |

-

|

|

"Usonia Homes, A Cooperative, Inc." Henken,

1947 |

|

"The Natural

House" Wright, 1954, page 196-207 |

|

"The Living City",

Wright 1958, pages 70-1 |

|

"Frank Lloyd

Wright’s Usonian

Houses: The Case for Organic Architecture"

Sergeant, 1976 |

| "Frank

Lloyd Wright, His Life and His Architecture" Twombly,

1979, page 338 |

|

"Frank Lloyd

Wright’s Usonian

Houses:

Designs for Moderate Cost One-Family Homes"

Sergeant, 1984 |

|

"Realization of Usonia:

Frank Lloyd Wright

in Westchester"

Beard, Henken, Henken, 1985 |

|

"Related items from the Usonian

Automatic Traveling Exhibition" 1987 - 1990 |

|

"Wright Seen Anew as an Architect of

Thoughts"

Goldberger, The New York Times, February 7,

1988 |

|

"Usonian

Automatic: Wright's Concrete Masonry" Hurd, Concrete

Construction Magazine, November 1, 1988 (PDF) |

|

"Frank

Lloyd Wright 'In The Realm of Ideas"

Hackett,

Seattle

Post-Intelligencer, October 5, 1989 |

|

"Usonia, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Design for

America"

Rosenbaum, 1997 |

|

"Usonian

Houses", Ehrlich, 2002 |

|

"Frank Lloyd Wright Usonian

Houses GA Traveler 005", Pfeiffer, 2002 |

|

"Westchester Magazine - Best Total

Concept. Usonia."

Epstein, October 2004, pages 66-67 |

|

"Frank Lloyd

Wright, Complete Works 1943-1959", Pfeiffer; Gossel,

2009, page 216-217. |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Modern Architecture, Being the Kahn Lectures for 1930", Wright, 1931. Of interest is the illustration that proceeds Chapter 5. The illustration is entitled "Bock Ateliers. Concrete. Slab Roof. Stone Washes and Water Table. Windows Wrapping Corners to Express Interior Space. 1902." Bock met Wright in 1892 while working for Adler & Sullivan. Bock’s first commission from Wright was for the Frieze on the third floor of the Heller Home (1896 - S.038). He also worked on other Wright projects including the Stork (1898) and Boulder (1898) for Wright’s own Studio, the Dana Residence (1902 - S.072), Larkin Building (1903 - S.093), Scoville Park Fountain (1903 - S.094), Unity Temple (1904 - S.096), Martin (1904 - S.100), City National Bank (1909 - S.155), and Midway Gardens (1913 - S.180) just to name a few. In 1902 Wright to design a home and studio for Bock. It was designed in concrete. This was two years before the concrete Unity Temple, twenty-one years before Wright’s first concrete block home, the Millard Residence (1923 - S.214), and 49 years before the first Usonian Automatic, the Adelman Residence (1951 - S.344). Wright included the concrete "Bock Ateliers" in his 1910 Wasmuth Portfolio Plate LXII. Although the 1902 window casements were most likely designed in wood, Wright slightly modified the 1931 window design to include mitered glass corners, a precursor to Wright’s 1951 Usonian Automatic Homes.