SUPPORT

THE WRIGHT LIBRARYPROCEEDS FROM EVERY SALE GOES TO SUPPORT THE WRIGHT LIBRARY.

CLICK TO ORDER.

Dr. Isadore & Lucille Zimmerman Residence (1950- S.333)

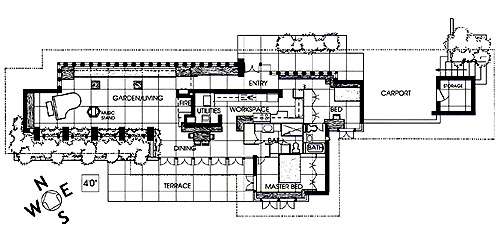

There is an abundance of information about the Zimmerman Residence. In the fall of 2007 I had the opportunity to visit the home and confirm that it truly is a work of art. From overall design to some of the smallest details. Designed in 1950, it was completed in 1952. John Geiger, an apprentice to Wright from 1947 to 1954, supervised the construction and lived with the Zimmerman’s for nearly a year during construction. He also helped supervise the “Sixty Years of Living Architecture” Wright’s retrospective exhibits in New York and Los Angeles (1953-1954). (I also had an opportunity to speak to John Geiger.) There are many classic Wright details. Wright used matte red brick, cast concrete, Georgian cypress and originally red clay roof tiles. The Cherokee red poured concrete floors are designed on a four foot grid system, it has a four foot cantilevered roof, and mitered glass windows that eliminate corners. Five sets of floor to ceiling wood framed glass doors open outward from the Dining Loggia to the Terrace. Bedroom windows also open outward. Clerestory windows bring light into the interior Workspace. The Zimmerman’s used Georgian cypress trim on both the interior and exterior of the house. There are also differences. The entrance is not hidden. The distinctive concrete cast window casings provide light and privacy. But the most unique aspect of this home are the brilliantly designed Garden Windows. A window within a window. I don’t believe this design appears in any other Wright homes. The glass windows are imbedded directly into the brick piers and wood ceiling. The lower pane bisects the planter. The wood trimmed window within a window frames the surrounding gardens designed by Wright. Pure genius.

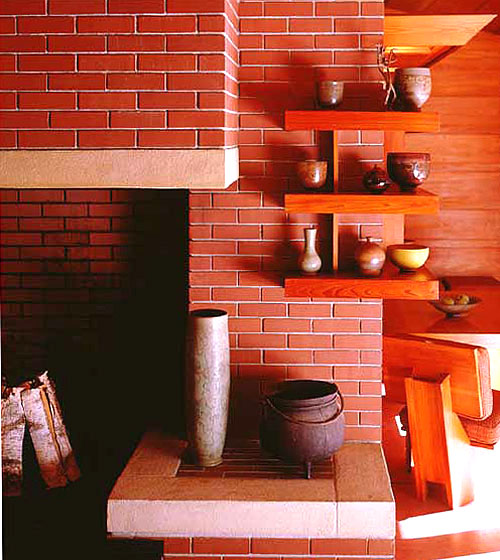

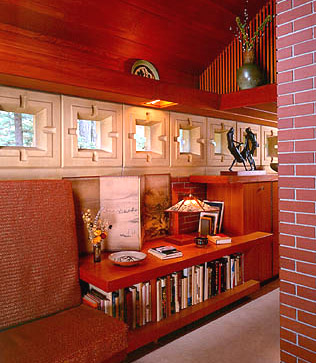

Tours of the interior are available, but photographing it is not. There is the large centrally located brick and cast concrete fireplace. Like many of Wright’s homes, he designed the furniture and dozens of built-ins. One of the most important piece is the Music Stand. According to the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, this is one of six quartet stands that are Wright-designed that are known to exist (two are at Taliesin, one is at Taliesin West, one is at the Dallas Public Library, and the sixth at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library in Austin, Texas), the one in the Zimmerman House is a variation of the "design matured with a more structurally sound construction than its predecessors." But we have located another at the Shavin Residence in Tennessee. In 1979 the Zimmerman Residence was listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Dr. Zimmerman past away in 1984. Four years later Mrs. Zimmerman past away. They left the house and everything in it, to the Currier Museum of Art in 1988. September 2007FLOOR PLAN EXTERIOR 2007 INTERIOR BIBLIOGRAPHY ARTICLES STUDIES Date: 1959

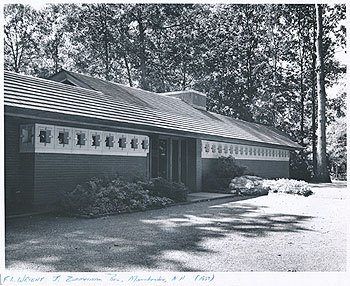

Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence, Manchester, NH, C 1959 (1950 - S.333).

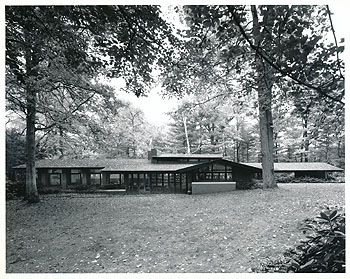

Description: Viewed from the East. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1950. The carport is on the far left out of the picture. A bedroom is on the left, entrance in the center, and living room on the right. Hand written on the face: "F.L. Wright: I. Zimmerman Res. Manchester, N.H. (1950)." Hand written on verso: "W 20, USA Arch. Wright." Also: "2117." Stamped on verso: "Photo: Wayne Andrews." Photographed by Wayne Andrews. Acquired from the archives of the University of Minnesota.

Size: Original 10 x 8 B&W photograph.

S#: 1377.109.0420Date: Circa 1959

Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence, Manchester, NH, C 1959 (1950 - S.333).

Description: Viewed from the East. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1950. The carport is on the far left out of the picture. A bedroom is on the left, entrance in the center, and living room on the right. Label pasted to board: "Arch. U.S.A. 20th cent. Frank Lloyd Wright. Res. I. Zimmerman, Manchester, N.H. (1950). East. Wayne Andrews #2117. Indiana University, Fine Arts Department." Photographed by Wayne Andrews. Acquired from the archives of the Indiana University.

Size: Original 9.5 x 7.5 B&W Photograph.

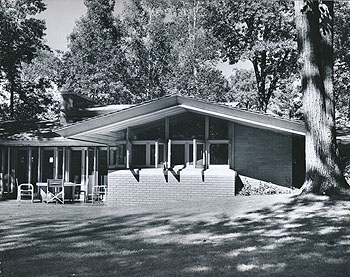

S#: 1377.127.0920Date: Circa 1959

Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence, Manchester, NH, C 1959 (1950 - S.333).

Description: Viewed from the South. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1950. The Living Room is on the left, Master Bedroom on the right. Label pasted to board: "Arch. U.S.A. 20th cent. Frank Lloyd Wright. Res. I. Zimmerman, Manchester, N.H. (1950). West. Wayne Andrews #2116. Indiana University, Fine Arts Department." Photographed by Wayne Andrews. Acquired from the archives of the Indiana University.

Size: Original 9.5 x 7.5 B&W Photograph.

S#: 1377.126.0920Date: 1988/1954

Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence, Manchester, NH, Circa 1988 (1950 - S.333).

Description: Exterior view of the Zimmerman Residence in 1954. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1950. Text on verso: "The Zimmerman House. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1950 for Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman, Manchester, NH. A Goft in 1988 to The Currier Gallery of Art. North Elevation. Photograph by Laurier C. Durette, 1954." Postcard published in 1988, photographed in 1954.

Size: 6 x 4.

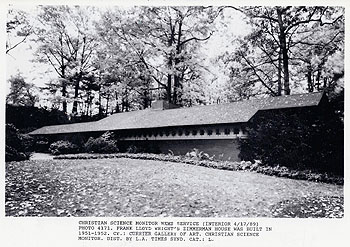

ST#: 1988.119.0821Date: 1989 Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence (1950 - S.333).

Description: Caption on face: "Christina Science Monitor News Service (4/17/89). Frank Lloyd Wright‘s Zimmerman House was built in 1951-1952. Cr. Currier Gallery of Art. Christian Science Monitor. Dist. By L.A. Times Synd.)" Stamped on verso: "The Seattle Times Library". Two copies. Acquired from the archives of the Seattle Times and the archives of the Christian Science Monitor.

Size: Original 7 x 5 B&W photograph.

ST#: 1989.75.0911, 1989.116.0920

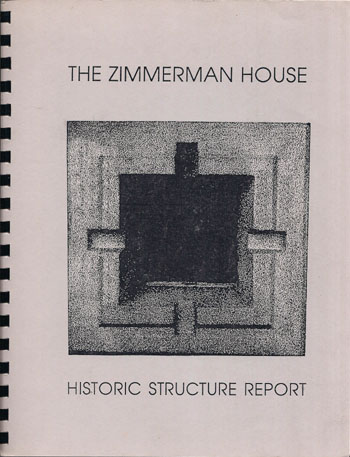

Date: 1989 Title: The Zimmerman House, Historic Structure Report (Comb Bound, Soft Cover) (Published by The Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, NH)

Author: Tilton + Lewis Associates, Inc. In collaboration with Donald Kalec; Edited by Carla Lind

Description: Report prepared for The Currier Gallery of Art detailing the condition and structure of the Zimmerman House. "Since the Zimmermans’ intent became know to the Currier, the Gallery has systematically collected and catalogued information about the residence, taped interviews with Lucille Zimmerman and the original contractor, Vincent Swanburg, now both deceased, with supervising Taliesin apprentice John Geiger and others. The documentation is exhaustive... It is such information that must be gathered before an accurate restoration of a property can be done. Only then can a restoration be based upon fact rather than assumptions. This report summarizes the information that has been gathered..." (First Edition)

Size: 8.5 x 11

Pages: Pp 62

ST#: 1989.84.0114

Date: 1990

Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence 1990 (1950 - S.333).

Description: Viewed from the Southwest. The Garden/Living Room is on the left. Wright designed a window within a window. Five sets of floor to ceiling wood framed glass doors open outward from the Dining Loggia to the Terrace. A short brick wall adds privacy to the Master Bedroom. The Carport is on the right. When the Zimmerman’s past away in 1988, they left the home and everything in it, to the Currier Museum of Art. Hand written on verso: "10/12/90. P.S22. Manchester, NH, Museum." Label pasted to verso: " View of the Zimmerman House from the south garden. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright (1950)."

Size: Original 10 x 8 B&W photograph.

ST#: 1990.145.1018Date: 1990 Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence Living/Garden Room 1990 (1950 - S.333).

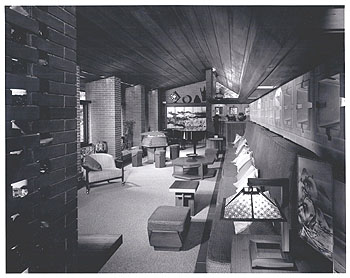

Description: Viewed from the Southeast. The fireplace is on the far left. A Wright designed Music Stand is seen in the center. Built-in seating on the right. A Taliesin lamp is is in the foreground on the right. When the Zimmerman’s past away in 1988, they left the home and everything in it, to the Currier Museum of Art. Hand written on verso: "10/12/90. Garden Room, Zimmerman House. The Currier Gallery of Art, 192 Orange St., Manchester, NH 03104." For more information on the Zimmerman Residence see our Wright Study.

Size: Original 10 x 8 B&W photograph.

ST#: 1990.108.0414

Date: 2004 Title: A Work of Art for Kindred Spirits, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Zimmerman House (Soft Cover) (Published by the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire)

Author: Levine, Neil; Startup, Hetty; Sundstrom, Kurt J.

Description: “Good architecture demands good clients. Creative, experimental architects like Frank Lloyd Wright require something more special. Their clients have to be devoted to the cause...” 6,000 copies published. (First Edition) For more information on the Zimmerman Residence see our Wright Study.

Size: 12 x 8

Pages: Pp 33

ST#: 2004.50.0907

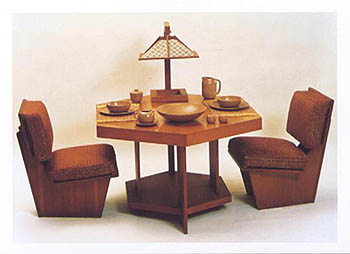

Date: Circa 2005 Title: Zimmerman Dining Room Table

Description: Back: "Frank Lloyd Wright (1967-1959). The Zimmerman House, 1950. Dining Table, Dining Chairs and Table Lamp, 1951-2. Cypress and cypress plywood. Bequest of Dr. Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman. The Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, NH. Published by Graphique de France, Boston, USA / Paris, France. WE100." (Three copies) For more information on the Zimmerman Residence see our Wright Study.

Size: 5.9 x 4.1

ST#: 2005.26.0907 - 2005.28.0907

Date: 2007 Title: The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Zimmerman House.

Description: The Currier Museum of Art presents: The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Zimmerman House. “The Currier Museum of Art offers you unique opportunity to explore the world of Frank Lloyd Wright. The Zimmerman House is the only residence in New England designed by the acclaimed American architect that is open to the public.” Tour information. Includes four photographs. Seven copies. For more information on the Zimmerman Residence see our Wright Study.

Size: 8.5 x 11

Pages: Pp 1

ST#: 2007.31.0907 - 2007.37.0907

Date: 2007 Title: The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Zimmerman House

Description: The Currier Museum of Art presents: The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Zimmerman House. “The Currier Museum of Art offers you unique opportunity to explore the world of Frank Lloyd Wright. The Zimmerman House is the only residence in New England designed by the acclaimed American architect that is open to the public.” Tour information. Includes five photographs. Ten copies. For more information on the Zimmerman Residence see our Wright Study.

Size: 5.5 x 8.5

Pages: 1

ST#: 2007.38.0907 - 2007.47.0907

Date: 2007

Title: Dr. Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman Residence, Manchester, NH, 2007 (1950 - S.333).

Description: Set of 28 photographs of the Zimmerman Residence. There are many classic Wright details. Wright used matte red brick, cast concrete, Georgian cypress and originally red clay roof tiles. The Cherokee red poured concrete floors are designed on a four foot grid system, it has a four foot cantilevered roof, and mitered glass windows that eliminate corners. Five sets of floor to ceiling wood framed glass doors open outward from the Dining Loggia to the Terrace. Bedroom windows also open outward. Clerestory windows bring light into the interior Workspace. The Zimmerman’s used Georgian cypress trim on both the interior and exterior of the house. There are also differences. The entrance is not hidden. The distinctive concrete cast window casings provide light and privacy... Continue...

Size: Set of 28 high res 8 x 10 digital images.

ST#: 2007.91.0520 (1-28)

See additional photographs...

See additional photographs...Zimmerman FLOOR PLAN Floor plan copyright 1993, “The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion” Storrer, William Allin, page 353. Exterior Photographs By Douglas Steiner, September 2007

There are many classic Wright details. Wright used matte red brick, cast concrete, Georgian cypress and originally red clay roof tiles. The Cherokee red poured concrete floors are designed on a four foot grid system, it has a four foot cantilevered roof, and mitered glass windows that eliminate corners. Five sets of floor to ceiling wood framed glass doors open outward from the Dining Loggia to the Terrace. Bedroom windows also open outward. Clerestory windows bring light into the interior Workspace. The Zimmerman’s used Georgian cypress trim on both the interior and exterior of the house. There are also differences. The entrance is not hidden. The distinctive concrete cast window casings provide light and privacy. But the most unique aspect of this home are the brilliantly designed Garden Windows. A window within a window. I don’t believe this design appears in any other Wright homes. The glass windows are imbedded directly into the brick piers and wood ceiling. The lower pane bisects the planter. The wood trimmed window within a window frames the surrounding gardens designed by Wright. Pure genius. Interior Images By J. David Bohl

Tours of the interior are available, but photographing it is not. There is the large centrally located brick and cast concrete fireplace. Like many of Wright’s homes, he designed the furniture and dozens of built-ins. I had the opportunity to view the interior of the home, but photography of the interior was not allowed.

These interior photographs are Copyright J. David Bohl and the Currier Museum of Art.

1: View of the centrally located brick and cast concrete fireplace, the Dining Loggia from the Garden/Living Room.

2: Centrally located brick and cast concrete fireplace with Wright designed shelves. The Dining Loggia with Wright designed furniture on the right. 3: Dining Loggia with Wright designed shelves and furniture. The Workspace is to the right. Four foot grids system is visible in the floor. 4: Built-ins viewed from the Garden Room, the entry is to the right.

5: Built-ins viewed in the Workroom. BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Frank Lloyd Wright: In The Realm of Ideas" Pfeiffer, Nordland, 1988, page 101. "GI 10: Global Interior #10: Houses by Frank Lloyd Wright 2" Text: Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks; Edited and Photographed: Futagawa, Yukio, 1990, pages 136-141. "Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph 1942-1950", Text: Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks; Edited and Photographed: Futagawa, Yukio, 1990, page 327-329. "Frank Lloyd Wright Selected Houses 7", Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks, 1991, page 104-119 "Architectural Monographs No 18: Frank Lloyd Wright" Heinz, 1992, page 120-121. "Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography" Secrest, 1992, page 470. "The Wright Style" Lind, 1992, page 45, 72, 116-117. "Frank Lloyd Wright: The Masterworks" Larkin, Pfeiffer, 1993, page 240-245. “The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion”, Storrer, William Allin, 1993, page 353. "Frank Lloyd Wright East" Heinz, 1993, page 44-47. "Frank Lloyd Wright and the Meaning of Material" Patterson, 1994, page 23, 96, 107, 207, 213. "Frank Lloyd Wright’s Dining Rooms" Lind, 1995, page 42-43. "Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fireplaces" Lind, 1995, page 52-53. "Frank Lloyd Wright Design" Costantino, 1996, page 108-109. "Frank Lloyd Wright" Thomson, 1997, page 146-149, 212-213, 217-218. "The Life & Works of Frank Lloyd Wright" Costantino, 1998, page 117-119, 168. "Frank Lloyd Wright - A Visual Encyclopedia" Thomson, 1999, page 356-357. "50 Favorite Furnishings By Frank Lloyd Wright" Maddex, 1999, page 58-59. "Frank Lloyd Wright Glass" Ehrlich, 2000, page 17, 42, 121. "The Vision of Frank Lloyd Wright" Heinz, 2000, page 248-249. "50 Favorite Houses By Frank Lloyd Wright" Maddex, 2000, page 110-111. "Frank Lloyd Wright: Inside and Out" Maddex, 2001, page 174-175. "Interiors, Frank Lloyd Wright at a Glance", Moor, Abby, 2001, page 60-63. "The Wright Space" Hart, 2001, page 78-79, 88-89, 181. "Frank Lloyd Wright Field Guide" Clayton, 2002, page 281, 284, 286-291. "Frank Lloyd Wright Elegant Houses, GA Traveler 006", Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks, 2002, page 208-227. "Usonian Houses, Frank Lloyd Wright at a Glance", Ehrlich, Doreen, 2002, page 66-71. "Wright-Sized Houses", Maddex, Diane, 2003, page 120-127. "A Work of Art for Kindred Spirits, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Zimmerman House", Levine, Neil; Startup, Hetty; Sundstrom, Kurt J., 2004 "The Wright Experience, A Master Architects Vision" Hunt, 2008, page 15, 92. "Frank Lloyd Wright American Master", Weintraub; Smith, 2009, pages 280-281. "Frank Lloyd Wright, Complete Works 1943-1959", Pfeiffer; Gossel, 2009, pages 270-271. Additional ARTICLEs A) "Music Stand", By Hetty Startup, Zimmerman House Site Administrator. B) "Wright's work, the Fellowship and more: An interview with John Geiger", By Mark Hertzberg, July 2, 2007 C) "Small is beautiful in Wright house", By Sacha Pfeiffer, The Boston Globe, October 11, 2007 MUSIC STAND

1: Music Stand. 2: Music Stand with Stools.

MUSIC STAND

By Hetty Startup

Images by the Currier Museum of ArtWhen Wright designed a house he typically created much of the furniture as well. The Zimmerman House is no exception, and its music stand contributes significantly to the building's domestic aesthetic and sense of modernity. However, as was often the case with Wright's furniture, it was not always considered very practical and was not "too popular with the professional musicians" using it (1). Wright's approach to design was intended to embrace the lives of his clients in more ways than one, and in this case, he wanted to support the Zimmermans' love of music and their plans for modest entertaining. Of the six quartet stands that are Wright-designed that are known to exist (two are at Taliesin, Wright's home and school in Wisconsin, one is at his winter retreat and residence called Taliesin West, in Arizona, one is at the Dallas Public Library, and the sixth at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library in Austin, Texas), the one in the Zimmerman House is a variation of the "design matured with a more structurally sound construction than its predecessors." (2)

The quartet stand is one of thirty-three pieces of furniture for the house. All of it was made of cypress and cypress veneer, a material Wright called "the wood eternal." He chose the same material for the home's interior walls and ceilings. Wright intended the music stand to form part of an integrated domestic space. Because he was also interested in organic forms that drew their inspiration from nature, the appearance of the music stand recalls that of an abstracted plant form. Rectangular in shape, it is also sculptural, and by far the most unusual piece of furniture in the room. The four facades of the stand contain ledges to hold sheet music. It is crowned with an ingenious, removable hood or tray with space for a small artwork, a plant or a vase of flowers. This hood also shades four small lights installed underneath the hood that help to illuminate the sheet music. Four stools accompany the stand.

Like the rest of the furniture in the Zimmerman House, the music stand was constructed in a Manchester manufacturing company, under the supervision of John Geiger, Wright's on site apprentice. Like the five other Wright music stands in existence, drawings were not necessarily made; if a drawing was requested,

Wright often incorporated any necessary modifications in terms of wood choice, form and detailing. In a recent correspondence, John Geiger recalled, "_ [the music stand] seemed such a natural in that [garden] room silhouetted against the grand piano. It went through a development period and no drawing existed for its finished form. [After it was finished,] Joe Fabris [another Taliesin apprentice] made a drawing from the finished product specifically for the Zimmermans." (3)

Wright's first designs for such a music stand date from the early 1930s when he made two versions in oak veneer and Philippine mahogany for the living room at Taliesin and the playhouse of the Hillside Home School. These were used by family members and also by his apprentices, once Hillside had been converted to use as his educational setting for apprentices called the Taliesin Fellowship. In his autobiography Wright states that his living room at Taliesin - where the music stand was installed next to a grand piano - acted as a stimulus to the apprentices to think about good design; everything was to be experienced from here, from views of the sheep on the hills outside to the "house decorations" indoors. The presence at the Hillside Playhouse of professional musicians and accomplished players amongst the apprentices themselves - where the second music stand was installed - also spurred interest in these spaces as a setting for all kinds of classical and folk repertoire. (4)

Dr. and Mrs. Zimmerman left all of the furniture with the house and made its entire contents a gift to the Currier Museum of Art in 1988. If the Zimmerman House itself is one of the most unusual and significant objects in the museum's collection, the music stand is arguably the most important object in the Zimmerman House.

NOTES

1. Email from John Geiger, the Zimmerman House Wright-appointed apprentice, July 12th 2004 to Hetty Startup, Zimmerman House Site Administrator.

2. E-mail from Oscar Munoz, Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, July 9th 2004 to Hetty Startup, Zimmerman House Site Administrator.

3. Email from John Geiger to Hetty Startup, July 12th 2004.

4. Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (New York: Horizon Press, 1977.)JOHN GEIGER

WRIGHT'S WORK, THE FELLOWSHIP AND MORE: AN INTERVIEW WITH JOHN GEIGER

By Mark Hertzberg, July 2, 2007

Photos and interview copyright Mark HertzbergJohn Geiger relaxes in his living room in West Los Angeles, reflecting on a lifetime of Frank Lloyd Wright. He does not fawn over Wright, and quickly steers the conversation to a critical look at the Taliesin Fellowship, the apprentice program which Wright started in 1932, when he was in dire financial straits. “Mr. Wright was a complicated man. I guess I’ve had some cause to reevaluate my relationship with him recently.”

Geiger, 85, was an apprentice to Wright from 1947 to 1954. He supervised construction of the Zimmerman House in Manchester, New Hampshire (1950), and helped supervise the “Sixty Years of Living Architecture” Wright retrospective exhibits in New York and Los Angeles (1953-4). He has an encyclopedic knowledge of Wright, an extensive Wright library and a stupendous computer data base that tracks every imaginable aspect of Wright’s work.

Geiger’s first exposure to Wright’s work was in 1938, when he took a course in Modern Architecture at the University of Minnesota. “There was Fallingwater on the screen. You can be a neophyte architect, and you see Fallingwater, and you know there is something there.” Geiger and a handful of classmates later visited Taliesin and Wright commissions in Chicago and Michigan.

Geiger then spent four years in the Army. “I went to Taliesin on the GI Bill. I didn’t have any illusions about Mr. Wright. It was a Faustian bargain. No apprentice expected a Nirvana of democracy. This was an autocracy, and we as apprentices, gave up a certain degree of autonomy for the privilege of being there. On the other hand you were free to leave at any time. There was nothing holding anybody there except your own desire to be there.

“I have concluded that the tie that binds was “In the Cause of Architecture” [a series of essays written by Wright for the Architectural Record]. We were, after all, participating in the creation of some of the greatest architectural monuments of the 20th Century. Even the lesser works have become national treasures. “In the Cause of Architecture” is what it was all about. It was not Wright as a personality. It was architecture.”

Geiger in his living room in West Los Angeles.

He left the Fellowship in 1954. “I don’t regret a day that I spent there, by the same token, it was time to go.” He decided to leave when he was building a temporary pavilion to house the “Sixty Years” show in Los Angeles. “The building [for the show] in New York had a pipe scaffolding framework.” The same structure was proposed for Los Angeles, but it was not earthquake proof. “The building department wouldn’t buy it.”

He made a new set of working drawings substituting welded pipe framing for scaffolding. “I just wrote Mr. Wright to tell him what we were doing. I never heard from him. I worked my tail off and we built the building in 21 days. The day before the show opens, Mr. Wright walks in at three in the afternoon, and moves the entrance. We had to tear out a chunk of concrete 12 feet square, remove 12 feet of existing wall and install 32 feet of new wall including the entrance doors. Morris Pynoos, the building contractor, was a jewel and by 11 the next morning, the walls had been moved and the fast setting concrete poured.

“Mr. Wright arrived unannounced about 3:00 that afternoon, dressed in black, ready for the 8:00 PM opening. He walked straight across the freshly poured concrete, which had set by that time, with no comment about the moved entrance. I guess he just took it for granted that the deed would be done. When he turned the corner into the main hall he was confronted by the gaping garage door opening instead of the slide screen he had expected to see. I knew that the slide show was important to him, so I had made plans to see that it would be ready for the opening that evening. I had given the foreman a drawing of the screen that morning and told him that no matter what was going on at 5:00 p.m., he was to stop whatever he was doing and build the screen frame and install the Translux screen I had calculated 45 minutes for him to do it.

“When Mr. Wright did not see the screen he started ranting and railing at me. I had worked my tail off to get the show open on target and was in no mood to put up with this temper tantrums. So I let him have his tantrum, but decided that unless he cooled down and treated me with a semblance of respect I would tell the foreman to forget about the screen. I approached him twice and he wouldn’t acknowledge me. On the third try, I got a grudging response and the deal was on. At 5:45 the screen was in place, the projector focused and the contractor’s wife, Rita, had arrived with a station wagon full of folding chairs for the viewers. The show was on.

“I never went back to the Fellowship. It was just time to go. I went back to Minneapolis to remodel my mother’s house. Wes (Peters) called me. He wanted me to come back to supervise the Milwaukee (Annunciation Greek Orthodox) church or do drawings for it. I told him I couldn’t. I felt absolutely no qualms about refusing to do that. I had done my thing and it was just time to go.”

Geiger talks about Wright’s expectation that people would bail him out financially. Wright is known for having borrowed money from people, including Peters, his son-in-law, apparently with no intention of paying them back. “He had absolutely no conscience about that at all. He was a user of people, there’s just no two ways about that.”

Then comes the inevitable discussion about Olgivanna Wright, the architect’s third wife. She was a proponent of the mystic Georgi Gurdjieff, who insisted that the apprentices join her in “Movements” or exercises that promoted Gurdjieff’s philosophy. The Fellowship was divided between apprentices loyal to Wright and more interested in architecture, and those loyal to Olgivanna, and willing to indulge her efforts to promote Gurdjieff’s ideas.

Roger Friedland and Harold Zellman write about this tension, which was particularly divisive to the Fellowship in the 1950s, in their controversial book “The Fellowship” (New York: Regan Books, 2006). Geiger remembers the tension well. He hosted a reception for the authors and for a number of apprentices last fall. He says that Zellman told him that Mrs. Wright “really hated” him. “I take that as a badge of honor. To generate that much enmity in her, I must have been doing something right.”

Wright died in 1959, but his former apprentices still invariably refer to him as Mr. Wright, never as Frank, and rarely as Wright. I asked Geiger about that. “When I am talking about Mr. Wright in a personal sense, it is Mr. Wright; in a generic sense (like a Wright building) it is Wright. Mr. Wright was essentially Victorian, his relationship with the apprentices was a formal one. It was not Frank this or that, or buddy-buddy.

“You would never call a client by her first name until after a job is done. That is how he treated the apprentices, like a business relationship with a client. He kept a formal relationship with them as opposed to Mrs. Wright. I heard Mr. Wright tell Mrs. Wright to stay out of their personal lives [although Friedland and Zellman are emphatic that she did not].”

Geiger returned to Los Angeles in 1955 and took his first real paid job with Daniel, Mann & Mendenhall for a few months. He then moved to Victor Gruen for a year or so. John Hill asked him to do the working drawings for the House Beautiful Pacesetter House, around 1957, and he used that pretext to establish a private practice. The practice lasted for four or five years but, Geiger, says, he didn’t have the aggressive personality necessary to promote himself, so he ended up in the retail business selling gifts and collectibles.

“It was always a balancing act between quality and solubility. It was good training for an architect. Your decisions were quickly verified as being valid or invalid.” He gained extensive experience working with computer data bases and developing mailing lists during his career, and uses that knowledge and those skills in his studies of Wright’s work. He has been retired for more than 20 years.

“I spend a lot of my time developing my data base, analyzing Frank Lloyd Wright and his work, both the man and his work. I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s no secret geometry played an important part in his work. As a way of examining the entire work I went through the Futagawa [Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer’s twelve-volume “Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph,” Edited and Photographed by Yukio Futagawa. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita, 1984-1988] volume by volume, and entered it into the data base. I forced myself to examine all the work in detail. Every drawing I entered, you have to look at for a couple of minutes. In doing so, I’ve come to the conclusion there is one basic geometric relationship inherent in all of Wright’s best work, and lacking in his lesser work and that is my (thesis).” He will not divulge what he thinks that relationship is. The answer will come in his book or on a web site he is developing.

He is asked his opinion about different buildings designed by Wright. “It’s a matter of comparison, obviously. I have all the work in a data base, and I’ve gone through and rated everything on a scale of 1-10. I took as a 5 the straightforward job that didn’t have a lot going for it, that was just a good straightforward job with no particularly outstanding characteristics. I've rated all the work on that basis. I've made a decision on the merit of all the residential work.

“For the tens, I've only reserved Fallingwater, the two Taliesins, Johnson Wax, and Jacobs #1. The Freeman House [which I had toured that morning] seven or eight. All the block houses have serious problems structurally. Curiously enough, I like the Ennis House best, of all the block houses. It’s got the most interesting spaces. The dining room is really an interesting space. It goes over into the entry way, it moves around, goes into the living room. It's just an interesting house I think. The Taliesin Fellows arranged a tour of all four block houses for 200 people in June, 1992. It was a serious undertaking, in one day.” Such a tour is not possible today because the houses are not all open to visitors anymore.

One of Geiger’s other great contributions to the Wright world is that he maintained the mailing list for the Taliesin Fellows. The list was invaluable to Friedland and Zellman, who he says, interviewed 90 of the apprentices in the decade they researched their book.

Geiger puts the Taliesin Fellowship in perspective, as discussion turns to Friedland and Zellman’s book about it. Many discussions of the book focus on the tension that revolved around Olgivanna and her emphasis on Gurdjieff, and on the chapter that discusses the sex lives of many of the apprentices. Geiger is emphatic about the importance of the apprentice program, no matter what shortcomings others may see in it.

“In my correspondence with a Wright scholar, it became clear that the contribution of the Fellowship ‘In the Cause of Architecture’ was of epic proportions. In the first 10 years they restored Hillside and opened the Playhouse in the first year. The parking terrace and Mr. Wright's balcony were also built. In three years they built Taliesin West from scratch. I visited it in the winter of 1941-42 and it was essentially complete. You also have to include Fallingwater, Johnson Wax, Jacobs #1, and numerous other first class houses. Were it not for the Fellowship none of this would have happened and Taliesin would be in ruins.”

The Fellowship was certainly a place for the apprentices to learn from Wright, but he did not always share information with them. Jaroslav J. Polivka was a Polish-born structural engineer who collaborated with Wright on projects in the 1940s. He had written a ‘fan letter’ to Wright, after reading that engineers had expressed doubts about Wright’s engineering of the cantilevered terraces at Fallingwater (doubts which, time has proven, were not misplaced).

Polivka devised a way to cantilever the entire ramp assembly from the stairwell/elevator core when he was working on early plans for the Guggenheim Museum. He applied the same engineering to designs for the stayed cable bridge for Wright’s unbuilt Pittsburgh Point Project. “The stayed cable bridge was a new concept in the US at that time and would not have been possible without Polivka,” says Geiger. But, Wright did not share Polivka’s idea with his apprentices.

Geiger learned that Wright did not share Polivka’s ideas, only recently. “I have to admit I was angry with Wright for not sharing this new concept with the apprentices. How did Mr. Wright pass this information on to the apprentices? The answer was that he didn’t. I concluded he felt absolutely no obligation to pass information on to apprentices or take them into his confidence. It changed how I viewed Mr. Wright. He said, ‘‘I’m not a teacher, I’m not here to teach you. You can see what I’m doing, and get what you can from observing what I do.” He did not spoon feed the apprentices as it were, take them into his confidence. It was the reverse. I think he went out of his way to not inform the apprentices. It was up to the apprentice to figure it out. The question really changed my outlook of Mr. Wright.”

He continues, “If you follow Wright's income from the sale of Japanese prints as documented in Meech's Frank Lloyd Wright and the Art of Japan (Harry Abrams, 2001), it becomes obvious that his main income for many years was from the sale of prints... The point is that after the loss of income from the sale of Japanese prints in 1920, economic life for Wright became difficult. The Fellowship rescued Wright from financial insecurity and allowed him to live a financially secure life from the post war years until his death. But the main contribution was “In The Cause of Architecture.” Imagine the architectural scene without Fallingwater, the Johnson Wax building and Taliesin West. It is unlikely that any of them would have happened without the Fellowship. No one, including Freidland and Zellman, seem to recognize this.”

He wonders what the “main attraction” was for many of the apprentices who joined the Fellowship, and why so many stayed for so long. “I have concluded that the answer to the first question is that the attraction was “In The Cause of Architecture” to use Mr. Wright's phrase. For the prospective apprentice it was the opportunity of a lifetime to participate in the creation of a world class architecture. It had nothing to do with Wright as a personality. It was all about the architecture and not to be missed. We were not indentured servants, as some scholars seem to think, or employees, but apprentices who made a conscious decision to participate in an endeavor that benefitted both society and ourselves.”

“I stayed seven years, which included supervision of the Zimmerman house, the New York and LA “Sixty Years” shows. They were exciting times and would not have missed them for the world. I have no regrets for my years at the Fellowship. In the 50's Mrs. Wright's influence increased and the focus changed from him to her and the quality of the work declined. But that is another story, as is why some people spent there entire adult life there.”

Curtis Besinger mentions Geiger in his autobiographical perspective about the Fellowship (“Working with Mr. Wright: What it was Like,” Cambridge University Press, 1997). Olgivanna Wright wanted the apprentices to help her prepare for a demonstration of Gurdjieff’s Movements in Chicago in June, 1953, while Mr. Wright wanted them to concentrate on the “Sixty Years” exhibit in New York. “John Geiger... has about had his fill of the ‘soul searching’ establishment that we are turning into...You see Mr. Wright’s philosophy and Mrs. Wright’s do not mix. As near as I can tell they are in direct opposition. The division of the effort of the Fellowship into two camps regarding Mr. Wright's show in New York and Mrs. Wright’s show in Chicago is an example of this.”

Geiger looks forward to refining his Wright data base and developing a web site of his own. He puts the conflicts at Taliesin in perspective. “I was four years in the Army, including two years in the South Pacific. I’d been around...I learned survival tactics in the Army, so Taliesin was a piece of cake.”

Geiger's library includes a first edition of the “Wendingen” collection of Wright's work, autgraphed by Wright. The formal title of the book is “The Life of the American Architect Frank Lloyd Wright,” published by C. A. Mees, Stanport, Holland, 1925. It consists of consecutive issues of the art magazine “Wendingen.” Geiger remembers, “I bought my copy from William Helburn in New York in January of 1944. I had just received my commission as 2nd Lieutenant and paid $125 for the book, which is $1,409 in 2006 dollars.” It is inscribed “To John Geiger at Taliesin - This now rare first edition - Frank Lloyd Wright”SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL

SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL IN WRIGHT HOUSE

By Sacha Pfeiffer, The Boston Globe, October 11, 2007

MANCHESTER, N.H. - Some neighbors called it "the chicken coop." Others likened it to a trailer because of its long, low-slung appearance.

But its new owners were ecstatic, calling it a "dream come true" and "the most beautiful house in the world."

Today, the Zimmerman House, designed by celebrated architect Frank Lloyd Wright, is one of New England's lesser-known architectural treasures. It's an immaculately preserved example of what Wright dubbed his "Usonian" design: compact, efficient, economical homes that were stylistically distinctive but also affordable for the middle class.

In 1950, however, when it was built on a residential street dominated by traditional Queen Anne and Colonial revival homes, the modernist structure was a jarring sight.

The horizontal, single-story, red brick house looks fortress-like from the street. A row of small windows, framed in pale yellow concrete and placed so high they almost touch the low-hanging roof, stretches across the front of the house like a belt. The clay tile roof is red, too, and resembles a runway with its wide eaves and irregular slope.

Inside, the ambience is strikingly different. The entry hallway is dark and narrow but leads to a 13-foot-high room flooded with natural light. The rear of the house is floor-to-ceiling windows that offer a panoramic view of a wooded backyard, blending into the natural landscape.

Situated on a three-quarter-acre lot, the house is less than 1,700 square feet - enough space for two bedrooms, two bathrooms, a dining area, a large living room, and a narrow galley kitchen. The ceiling is made of golden-orange Georgia cypress, and the floor is brick-colored concrete.

Earth tones also characterize the furnishings, including textiles, carpets, and artwork. Most of the cabinets, shelves, and seating are built into the walls.

Although it is nearly 60 years old, the house is remarkably well-preserved, largely because its only residents were Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman, who lived in it from 1952 until they died. The couple bequeathed it to Manchester's Currier Museum of Art, which took it over in 1988.

That makes it one of the few Wright buildings in the country owned and operated by an art museum, and the only Wright home in New England open to the public. It typically receives 4,000 to 5,000 visitors a year.

"I think of it as the largest and most important object in our collection," said Andrew Spahr, chief curator of the Currier, which considers the house part of its permanent holdings, "and it has the added challenge that it lives outdoors, so it comes with all the joys of home ownership."

The Zimmermans gave the house to the Currier because they wanted it to be preserved as a work of art. When the couple - he was a urologist, she was a nurse - were ready to downsize from their 13-room home in Manchester, they contacted Wright to ask whether he would build them a house that would be radically different from any other in Manchester.

In a letter to the architect, who died in 1959, they explained they wanted "a small, spacious, simple home... that would require the least housekeeping and which would allow for privacy and outdoor living."

Additional Wright Studies SEE ADDITIONAL WRIGHT STUDIES Frank Lloyd Wright's First Published Article (1898) Photographic Chronology of Frank Lloyd Wright Portraits "Frank Lloyd Wright's Nakoma Clubhouse & Sculptures."

A comprehensive study of Wright’s Nakoma Clubhouse

and the Nakoma and Nakomis Sculptures. Now Available.

Limited Edition. More information.Text copyright Douglas M. Steiner, Copyright 2014, 2020.