- Wright Studies

Banff National Park Pavilion, Banff, Alberta (1911) (S.170)

In 1955, when Wright was asked his opinion on Canadian architecture, he responded, "Just as fossilized as that in the States. These Canadian houses are little boxes for which people pay three times what they are worth. They are a place for making ham and eggs and having a good snore. The only architectural exceptions are found in Montreal, whose buildings are more gracefully human, and a modest little pavilion which I once built in Banff." (Lib p24). This past summer we had the opportunity to visit the town of Banff, Alberta. The goal was to locate the original site of the Banff National Park Pavilion (S.170).

Although Alberta did not join the Canadian Federation until 1904, a key to Banff's growth was British Columbia and the Canadian Pacific Railroad.

In July of 1871, British Columbia became the fifth Province to join the Canadian Federation with the promise that the Canadian government would construct a national railway, joining it with the Eastern Provinces. The railway finally passes through the Banff area in 1883. That same year hot springs are discovered in Banff on Sulfur Mountain and railroad workers staked a claim. A year later in 1884, Lord Steven, a former Canadian Pacific Railroad director, christened the area "Banff" after his birthplace, Banffshire in Scotland. In 1885 the Canadian government set aside a reserve in the Banff area. Two years later it established the Rocky Mountain Park, Canada's first National Park. It was not until 1930 that it was renamed the Banff National Park. To encouraged tourism in the area, the Canadian Pacific Railway built the Banff Hot Springs Hotel in 1888, promoted as an international resort and spa. As the area grew as a tourist destination, so did the town of Banff. Support also came from the Canadian Government, and in 1911, Ottawa commissioned a "Park Shelter" in Banff.

The "Park Shelter" was designed by Wright in association with Francis C. Sullivan for the Department of Public Works and the Banff National Park. Sullivan was born on July 2, 1882 in Kingston, Ontario. He was eighteen, when his family moved to Ottawa, Ontario, the capital of Canada.

According to Chisholm, in 1903, at 21, Sullivan became a draftsman for Ottawa architect Moses Edey. In 1905 he moved to the office of Alex McDougall, and in 1906 became an architect in the office of E. L. Horwood. A year later, he left Ottawa for California and was in the States for approximately a year. It was most likely during this period that he met Wright. Years later, in 1917, Wright would write, "Francis Conroy Sullivan. An Architect Ahead of His Time... I am your friend because you have tried hard to do something superior in your work and tried to do it honestly."

In 1908, Sullivan was back in Ottawa working for the Canadian Department of Public Works in the Chief Architect's office where he was employed for three years.

His connections with the Canadian Public Works Department in Ottawa, the capital of Canada, enabled him, in 1911, to start his own Architectural firm. One of his first commissions was a "Park Shelter" at Banff.

One question begs to be asked. Why would Sullivan not take the commission solo? It was most likely his admiration for Wright, the opportunity to work with and promote Wright in Canada, and a desire to add weight to his proposal by associating with one of Americas' premier Architects.

There is no doubt that the design of the Pavilion was Wright's. But he credits the association. Wright's Pavilion drawings read: "Park Shelter At Banff. Frank Lloyd Wright And Francis C. Sullivan, Associate Architects. Ottawa, Canada."

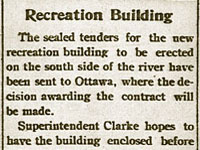

Two years after the "Shelter" was designed, construction finally began. In an article dated October 18, 1913, the Banff Craig and Canyon reported that "Work was started on the New $20,000 Recreation Building... The structure will be of rustic frame, one story in height, with cement and rubble foundation. The outside dimension will be 50 x 200 feet. The interior will contain a general assembly or lounging room 50 x 100 feet, with a ladies' sitting room 25 x 50 feet at one end and a sitting room for gentlemen, 25 x 50, at the other end. Dressing rooms, lockers, etc., and provided for also three cobblestone fireplaces."

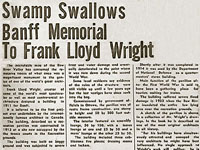

Whether initially purposed by Ottawa or by the local residence, one can only surmise the intent and vision of the Canadian government in support of the pavilion, and the outline submitted to Wright and Sullivan in the original proposal. A magnificent spot for tourist to gather, participate in a few summer sports, picnic, lounge and relax with a cup of afternoon tea, during the summer when it is possible to utilize the facility. An elegant facility, with art-glass windows, situated to take in the spectacular panoramic views. A building that would draw tourists to the area, represent the Canadian Government and be worthy of Ottawa's support. It was clear from a report in the Banff Craig and Canyon, dated December 16, 1913, that the residence of Banff envisioned a more practical facility. "...but the building is suitable for a very few summer sports, picnicers' lounging place and drinking of afternoon tea, during four months out of the year. The original plans, as outlined by men who would use the building and presumably know something of what was required, called for a building containing accommodations for curling, hockey and all kinds of winter sports, and would have cost very little if any more than the one now under construction. These plans were sanctioned by the people of Banff at a mass meeting held in the National Park theater, but their wishes and desires were, as usual, ignored by the 'over lords' at Ottawa, who imagine they are wiser as to conditions in Banff than those who live and have their being here."Incensed residence were not the only problems the pavilion struggled with. It was built in a boggy, swampy area that experienced extensive flooding. The Banff Craig and Canyon, dated July 10, 1920 reported that "The grounds in front of the recreation building were under water last week, and it was possible for a man, if so inclined. to wade out to the building, sit on the steps and fish." Shortly after it was completed, during the first World War, the building was utilized as a Quarter Master's Stores by the Department of Defense. After the war it was used as proposed by the ever growing tourist population, and the residence of Banff. The widespread flooding of the Bow River in1933 covered the entire low lying area near the recreation grounds causing severe damage to the pavilion. Water damage, which caused its eventual deterioration, was too brutal. In 1938, after only 25 years of use, nature won out. The Pavilion was demolished. Although the Pavilion no longer exists, the existing grounds today are highly utilized as a recreation area today.

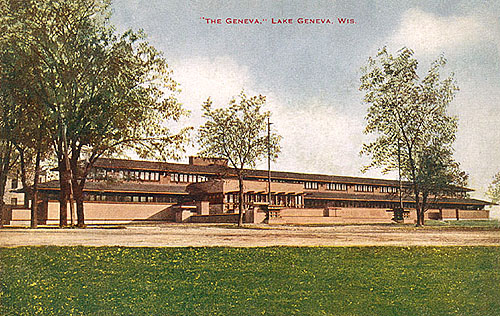

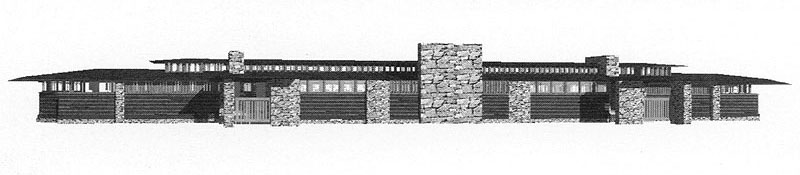

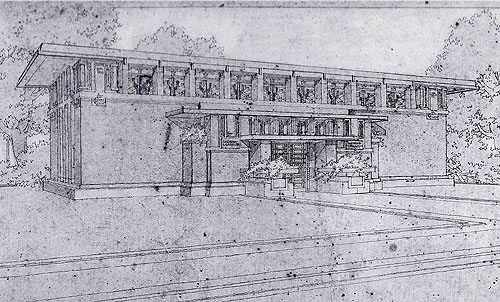

The Pavilion was similar in look and feel to the Como Orchard Summer Colony Clubhouse (1909 S.144), the Bitter Root Inn (1908 S.145), and the Lake Geneva Inn (1911 S.171). Long and narrow, strong horizontal lines, low-pitched roof, broad overhanging eaves, horizontal rows of leaded or mullion divided glass windows and glass doors. But it comes closest to the River Forest Tennis Club (1906 S.119).

There were many classic Prairie styled Wright details in the Pavilion. The basic material was wood, with horizontal board and batten siding, stone and glass. There were strong horizontal lines, the low-pitched roof, broad overhanging eaves, horizontal rows of art-glass windows and doors, three prominent fireplaces and chimneys, clerestory windows, customized light fixtures, balconies and terrace. There were built-in piers or columns that could have been designed for planters or large vases like many of his buildings at that time. The Front side had two covered porte cochere (Carriage Entryways) with stairs that lead up into the pavilion. Doors opened outward from the expansive interior "Pavilion" to an open Terrace which ran half the length of the building. There was a Ladies Retiring Room, Facilities and Kitchen. The other end was the Men's Retiring Room, Facilities and a room for the caretaker.

In 1911, not only did Wright and Sullivan collaborated on the "Park Shelter", but also an uncompleted project, a Railway Station for the Banff National Park (Mono3, p 196).

A third collaboration for the two was the 1913 Pembroke Public Library (Mono3, p 235), one of the 125 Canadian libraries funded by the Andrew Carnegie Foundation. Sullivan drew on Wright to design the Library but these first drawings were rejected due to the estimates cost of production. Sullivan redesigned the Library, adopting many of Wright's prairie styled elements. There is some confusion as to the actual date of this project. In his extensive article on the life of Sullivan, Chisholm writes that this project was "One of his first commissions..." and dates it at 1911. Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer and The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation date the project at 1913. The Ontario Heritage Properties Database dates the actual construction at 1914. I would lean toward Pfeiffer and the Foundation on this one. Again in 1914 they collaborated on another Project, a Ladies Kiosk in Ottawa (Mono4, p 16). Of the four Projects, only the Banff National Park Pavilion was built.

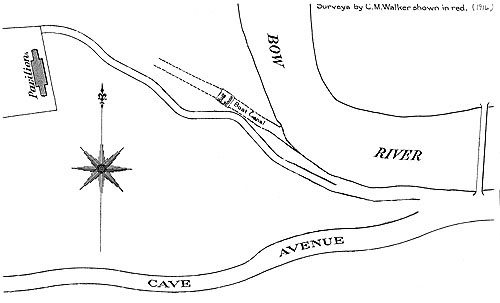

Our first stop in Banff was the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, located in downtown Banff. Among the numerous items related to the Pavilion, the Archive Department contained a major key. A 1916 survey by C. M. Walker. The museum also contains some of the only photographs that document the Pavilion.

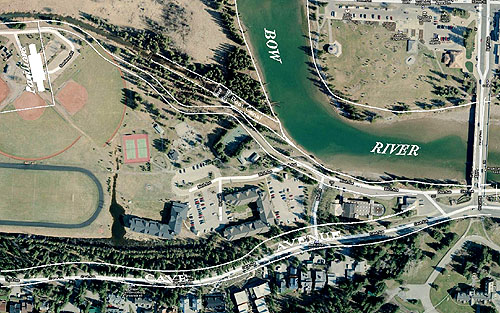

The 1916 survey records the curve in the Bow River, the Bridge, still crossing in the same spot, Cave Avenue, the Boat Canal and Boat House, and most importantly, the location and positioning of the Pavilion, all at a scale of 150:1. When superimposing it over an areal view from Google, at the same proportion, we are able to locate the original site of the Pavilion. From the center of the Pavilion, it measures approximately 870 feet to the edge of the Bow River and approximately the same distance to the center of Cave Avenue. Of note is the shallow Boat Canal that lead to a Boat House, and continued on, ending very close to the original location of the Pavilion. Could this Canal have increased the flooding in the immediate vicinity of the Pavilion, eventually accelerating its deterioration?

Wright and Sullivan's relationship continued, and in 1916 Sullivan closed his firm, and left Canada. Chisholm writes, "...His first stop was Taliesin where he worked on drawings for the Imperial Hotel project. ...Wright offered Sullivan a job as supervisor of construction in Tokyo." He declined due to health. "In 1928... Wright invited Sullivan to join his staff in Arizona... In March of 1929 Sullivan collapsed... was rushed to the hospital in Phoenix... He was dead at the age of 47. Wright himself made the arrangements to return the body to Canada... In 1951... Wright wrote of his Canadian disciple ‘Fras’ - as we called him - was a brave fellow and a competent one. His end was tragic."

The Banff Pavilion was a excellent example of Wright's work. Although nothing remains of the blending of prairie architecture and art-glass in the splendor of the Banff National Park, as you stand in the area where the pavilion once stood, inhale the breathtaking surroundings, it takes little imagination to experience what tourist and residence experienced 100 years ago. But if not for the imagination and collaboration of Sullivan and Wright, the Banff National Park pavilion would never have been conceived and built.

Text by Douglas M. Steiner, Copyright June 2010.Locating Banff National Park Pavilion Site Locating the Boat Canal River Forest Tennis Club (1906) Original Perspective 1911-12 Original Floor Plan Photographs of the Original Site, 2010 Historic Photographs 3D Images Excitement, Resentment, Disaster, Genius, Resurrection Wright & Sullivan Footnote Biographical Information Books & Articles

Locating the Banff National Park Pavilion Site

Our first stop in Banff was the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, located in downtown Banff. Among the numerous items related to the Pavilion, the Archive Department contained a major key. A 1916 survey by C. M. Walker. The museum also contains some of the only photographs that document the Pavilion.

The 1916 survey records the curve in the Bow River, the Bridge, still crossing in the same spot, Cave Avenue, the Boat Canal and Boat House, and most importantly, the location andpositioning of the Pavilion, all at a scale of 150:1. When superimposing it over an areal view from Google, at the same proportion, we are able to locate the original site of the Pavilion, approximately 900 feet from the Bow River. Of note is the shallow Boat Canal that lead to a Boat House, and continued on, ending very close to the original location of the Pavilion. Could this Canal have increased the flooding in the immediate vicinity of the Pavilion, eventually accelerating its deterioration?

Among the numerous items related to the Banff Pavilion in the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, the Archive Department contained a major key. A 1916 survey by C. M. Walker. The survey records the curve in the Bow River, the Bridge, still crossing in the same spot, Cave Avenue, the Boat Canal and Boat House, and most importantly, the location and positioning of the Pavilion. Courtesy of Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies. 1: Aerial view of the site in 2010. Courtesy of Google Maps, Terra Metrics. 2: When superimposing the survey over the areal view, we are able to locate the original site of the Pavilion, approximately 900 feet from the Bow River. Of note is the shallow Boat Canal that lead to a Boat House, and continued on, ending very close to the original location of the Pavilion. Could this Canal have increased the flooding in the immediate vicinity of the Pavilion, eventually accelerating its deterioration? 3: Detail of the immediate area surrounding the site of the Pavilion. From the center of the Pavilion, it measures approximately 870 feet to the edge of the Bow River and approximately the same distance to the center of Cave Avenue. The original road leading to the Pavilion from the bridge has been abandoned. Note the shallow Boat Canal that runs from the Bow River, ending very near the North end of the Pavilion. Could this Canal have increased the flooding in the immediate vicinity of the Pavilion, eventually accelerating its deterioration? 3a: Same detail as above, but with drawing of Pavilion superimposed over aerial 4: Detail of the existing Boat Canal and site of the original Boat House. The original road leading to the Pavilion from the bridge has been abandoned.

Locating the Original Boat Canal, June 2010

We began our search by locating the Boat Canal which begins approximately 800 feet from the Banff Avenue Bridge. One side of the canal is still lined with rocks. The Boat House was located approximately 250 feet from the Bow River's edge. By rough calculation the dimensions of the Boat House were approximately 50 x 60 feet. Interestingly, about 300 feet from the edge of the river we located the remnants of a pole. A corner post? An old power pole bringing electricity to the Boat House? As we continued on down the canal close to the ball fields and stables, there was still standing water and areas that were very marshy. Could this explain Image 7? (continued...) According to Sinclair and Walker...

River Forest Tennis Club (1906 S.119)

When the River Forest Tennis Club caught fire and burned in 1905, Wright was tapped to redesign their building. Although their have been many additions, including a move in 1920, The original design was a precursor to the Banff Pavilion.

Much can be gained by studying the plans of the River Forest Tennis Club. "Wright referred to the (Banff) pavilion as a more substantial version of the River Forest Tennis Club" (LWp116).The Tennis Club was 204 feet long, the Pavilion was 200. One end included a Ladies Locker Room and a Kitchen. The other end a Men's Locker Room. The three Fireplaces included built-in seating. Doors opened outward from the expansive interior, in essence, removing the wall which lead to an open Terrace which ran more than half the length of the building. Wright... (continued...)

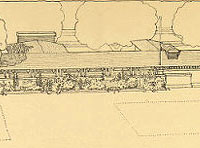

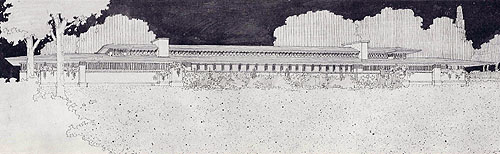

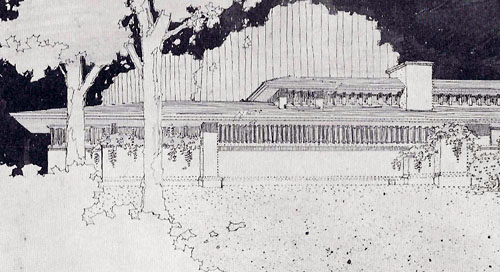

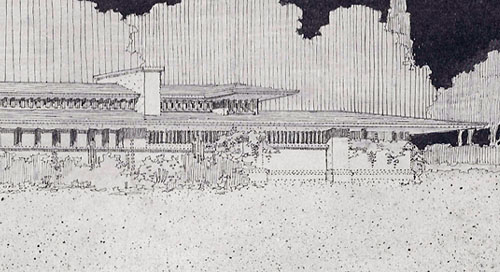

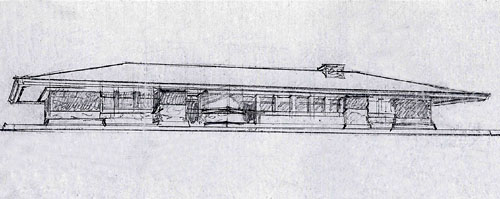

Wright's Original Perspective 1911-12

One of the few drawings of the Banff Pavilion can be found in "The Drawings of Frank Lloyd Wright", 1962, by Arthur Drexler. Published for the Museum of Modern Art by Horizon Press, New York. It was published for an exhibition of original Frank Lloyd Wright drawings held at the museum from March 14 to May 6, 1962. "Plate 42. Banff National Park Pavilion, Canada. 1911-12." The notes read: "Perspective. 7 1/8 x 21 1/8". Black ink and pencil shading on opaque paper. Inscribed at lower left: Banff Pavilion Park in Canada for Canadian Pacific Rwy. FLlW / 1911-12. F 1302.01)" Also published in "Frank Lloyd Wright In His Renderings, 1887-1959", Pfeiffer, 1991, Plate 51. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Horizon Press.

Wright's original rendering indicates stucco siding rather than "board and batten" which was added to the original plans and used in construction. Stucco was used in the construction of the Lake Geneva Hotel (see below) (S.171), Wright's next project, also designed in 1911. Other Prairie styled Wright details included strong horizontal lines, low-pitched roof, broad overhanging eaves, horizontal rows of art-glass windows and doors, prominent chimneys, clerestory windows, enclosed balconies. There were built-in piers or columns designed with planters or large vases like many of his buildings at that time. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Horizon Press. Detail of Wright's original rendering indicates stucco siding rather than "board and batten" which was added to the original plans and used in construction. Other Prairie styled Wright details included strong horizontal lines, low-pitched roof, broad overhanging eaves, horizontal rows of art-glass windows and doors, prominent chimneys, clerestory windows, enclosed balconies. There were built-in piers or columns designed with planters or large vases like many of his buildings at that time. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Horizon Press. Detail of Wright's original rendering indicates stucco siding rather than "board and batten" which was added to the original plans and used in construction. Other Prairie styled Wright details included strong horizontal lines, low-pitched roof, broad overhanging eaves, horizontal rows of art-glass windows and doors, prominent chimneys, clerestory windows, enclosed balconies. There were built-in piers or columns designed with planters or large vases like many of his buildings at that time. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and Horizon Press. . "The Geneva," Lake Geneva, Wis. This may be one of the earliest images of the Hotel Geneva. Published by V. O. Hammon Co., Chicago, IL. Circa 1912. See our Wright Study on the Lake Geneva Hotel.

Much can be gained by studying the plans of the River Forest Tennis Club (S.119) designed by Wright in 1906. It settles the questions where Wright or Sullivan was responsible for the design of the Banff Pavilion. "Wright referred to the pavilion as a more substantial version of the River Forest Tennis Club" (LWp116). The Tennis Club was 204 feet long, the Pavilion was 200. The Pavilion was about 50 feet wide in the center. The interior Pavilion was approximately 96 by 36 feet wide. There were two covered Porte Cochere (Carriage Entryways), and three Fireplaces. The left side included a Ladies Retiring Room, two Balconies and a Kitchen. The right included a Check Room, a Men's Retiring Room, two Balconies and a Caretaker's Room. The Fireplace Nook and Alcoves on either side included built-in seating. Doors opened outward from the expansive interior, in essence, removing the wall which lead to an open Terrace which ran half the length of the building. Wright designed each end by rotating a square 90 degrees. One distinctive design element Wright used in the Tennis Club and repeated in the Pavilion may have been unique to these two buildings. On either side of the Men's and Women's Locker rooms was a elongated row of Balustrated windows, or as Wright specified in the Tennis Club, 4"x4" Vertical Spindles with glass between. This allowed natural light in, while providing a measure of privacy. This design was repeated in the Pavilion, on either side of the Men's and Women's Retiring Rooms, as-well-as either side of the Fireplace in the Nook. Although not indicated in the drawings, photographs show this element was repeated on the interior of the pavilion to enclose the fireplaces and add a measurer of intimacy, much like his tall back chairs surrounding some of his dining room tables.

RIVER FOREST TENNIS CLUB (1906) Original floor plan copyright 1958, “Frank Lloyd Wright To 1910” Manson, page 171. Modified by Douglas M. Steiner from original drawings, copyright 2010.

BANFF NATIONAL PARK PAVILION (1911) Illustration drawn from original plans by Douglas M. Steiner and is a close representation. Copyright 2010.

Photographs of the Original Site, June 2010

Our first stop in Banff was the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, located in downtown Banff. Among the numerous items related to the Pavilion, the Archive Department contained a major key. A 1916 survey by C. M. Walker. The museum also contains some of the only photographs that document the Pavilion.

There are different report as to the exact location of the original Pavilion. The Banff Crag and Canyon, December 16, 1964,places it at the "site now occupied by the tennis courts..." Other reports place it by the shelters.

The 1916 survey records the curve in the Bow River, the Bridge, still crossing in the same spot, Cave Avenue, the Boat Canal and Boat House, and most importantly, the location and positioning of the Pavilion, all at a scale of 150:1. When superimposing it over an areal view from Google, at the same proportion, we are able to locate the original... (continued...)

Courtesy of the Whyte Museum Courtesy of the Whyte Museum Unless noted, photographs and text copyright Douglas M. Steiner, 2010.

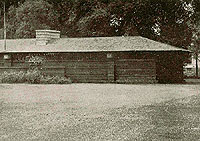

Historic Images of the Banff National Park Pavilion

Very few photographs exist that document the Banff National Park Pavilion. The Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, located in downtown Banff has the largest collection of items related to the Pavilion. Among the items are some of the only photographs documenting its approximate twenty-five years of existence. Unless noted, photographs courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies... (continued...)

Photographs courtesy of the Whyte Museum 3D Images of the Banff National Park Pavilion

"Frank Lloyd Wright’s Banff Pavilion: Critical Inquiry and Virtual Reconstruction. Using historical research and advanced computer technology, a long-forgotten Canadian structure, demolished in 1938, was described, its design and construction analyzed, and a 2D/3D model created." Brian Sinclair and Terence Walker produced an in-depth analysis, from original drawings, and created a 3D computerized model. They wrote one of the most complete description of the construction of the Pavilion. Published in the APT Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2/3. 1997... (continued...) Illustration courtesy of Sinclair and Walker. Excitement, Resentment, Disaster, Genius, Resurrection: Banff Crag & Canyon

Excitement, Resentment, Disaster, Genius, Resurrection. Within the archives of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies in Banff, Alberta, are a collection of news clippings from the Banff Crag & Canyon, which offer a glimpse into the attitude of the local residence toward the decisions of the Canadian Government and the Banff Pavilion.

Although Alberta did not join the Canadian Federation until 1904, a key to Banff's growth was British Columbia and theCanadian Pacific Railroad. In July of 1871, British Columbia became the fifth Province to join the Canadian Federation with the promise that the Canadian government would construct a national railway, joining it with the Eastern Provinces. The railway finally passes through the Banff area in 1883. That same year hot springs are discovered in Banff on Sulfur Mountain and railroad workers staked a claim. A year later in 1884, Lord Steven, a former Canadian Pacific Railroad director... (continued...)

Photocopy courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, Banff, Alberta.

Wright and Sullivan

In 1911, not only did Wright and Sullivan collaborated on the "Park Shelter", but also an uncompleted second project, a Railway Station for the Banff National Park (Mono3, p 196). A third collaboration for the two was the 1913 Pembroke Public Library (Mono3, p 235), one of the 125 Canadian libraries funded by the Andrew Carnegie Foundation. Sullivan drew on Wright to design the Library but these first drawings were rejected due to the estimated cost of production. Sullivan redesigned the Library, adopting many of Wright's prairie styled elements. There is some confusion as to the actual date of this project. In his extensive article on the life of Sullivan, Chisholm writes that this project was "One of his first commissions..." and dates it at 1911. Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer and The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation date the project at 1913. The Ontario Heritage Properties Database dates the actual construction at 1914. I would lean toward Pfeiffer and the Foundation on this one. Again in 1914 they collaborated on another Project, a Ladies Kiosk in Ottawa (Mono4, p 16). Of the four Projects, only the Banff National Park Pavilion was built.

Not only did Wright and Sullivan collaborated on the "Park Shelter", but also an uncompleted second project, a Railway Station for the Banff National Park. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. A third collaboration for Wright and Sullivan was the 1913 Pembroke Public Library, one of the 125 Canadian libraries funded by the Andrew Carnegie Foundation. Sullivan drew on Wright to design the first drawings for the Library. Courtesy of Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Wright's first designs for the Pembroke Public Library were rejected due to the estimated cost of production. Sullivan redesigned the Library, adopting many of Wright's prairie styled elements. Photograph courtesy of Padraic Ryan. Footnote

On a footnote, the only trace of Wright's design in the Banff Recreational grounds is a recent addition. A public washroom reminiscent of Wright's original design. Wright once said he would never patent the wall mounted lavatory he designed for the Larkin Building. He did not want to be remembered for designing a toilet. Not sure he would be thrilled with this. But he may have had a good chuckle.

Additional Biographical Information and Reading

Frontier Guide to Enchanted Banff and Lake Louise

1979 (Second Edition)

Frontier Publishing, LTD.

"The old tourist pavilion at Banff was a masterpiece of architecture. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and believed to be the first major undertaking in Canada by the celebrated architect..."Frank Lloyd Wright - The Banff Pavilion

A3, Art and Architecture - March 1984

Ferrari, Drew

"...Recently, the Banff Pavilion Committee was formed with the goal of the pavilion’s reconstruction, to be part of the 1985 centennial celebrations in Banff national Park..."Francis Conroy Sullivan. An Architect Ahead of His Time

The Beaver, Exploring Canada’s History, December 1987 - January 1988

Chisholm, Dorothy

"‘I am your friend because you have tried hard to do something superior in your work and tried to do it honestly.’ In these lines from a letter written around 1917 American architect Frank Lloyd Wright paid tribute to a brilliant, eccentric and neglected Canadian architect named Francis Conroy Sullivan... In 1911 they worked together on the Pembroke Public Library project."Frank Lloyd Wright’s Banff Pavilion

APT Journal, Vol. 28, No. 2/3. 1997

Sinclair, Brian R.; Walker, Terence J.

"Critical Inquiry and Virtual Reconstruction. Using historical research and advanced computer technology, a long-forgotten Canadian structure, demolished in 1938, was described, its design and construction analyzed, and a 2D/3D model created."A Hostel in the Mountains: Contemporary Construction in the Canadian Rockies

1998

Howiett, Jeff

"As we re-examine the human presence in our national parks, it is important to consider how the built environment can assist the appreciation and preservation of our natural surroundings."