|

|

|

|

Introduction Presentation

Drawing Drawings

Window Designs

Historic Photographs

Destruction

Replaced

Track Map

Related Items

Related Books |

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction |

|

|

|

|

Little has been written, and I

have to admit, I knew nothing about the short lived Stohr

Arcade. So when I stumbled upon a photograph, I was

surprised and intrigued. I thought I was aware of most of

Wright's work.

Peter C. Stohr (1859-1912) was born in New

York City in 1959. In 1890, at the age of 31, he married

Julia A. Collins. She was born in 1862 in Toledo, Ohio, the

daughter of Jasper P. Collins and Mary A. Collins. Peter

began is career in the railway business as an office boy for

the Rock Island Railroad. In 1887, he was a General Eastern

Agent for the Minnesota and Northwestern Railroad Company

(1). By 1891, Peter was an officer for the

Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railway, working as a

General Freight Agent in Chicago, Illinois (2).

In 1892, the railroad was reorganized under the name of

Chicago Great Western Railway. By 1895 he had relocated to

the St. Paul office where at the age of 36, a daughter was

born. Julia B. Stohr became a well known landscape and

portrait artist. (JB). In 1897 Peter

continued as an officer with the Chicago Great Western

Railway as a General Freight Agent in the St. Paul office

(3). From 1899 to 1904 the Stohrs lived at 502

Grand Hill, St. Paul, Minnesota

(502). By 1901

Peter had been promoted to Traffic Manager in the St. Paul

office as an officer with the Chicago Great Western Railway

(4).

In 1905 the Stohrs moved back to Chicago

when he was hired by Edward H. Harriman as an Assistant

Traffic Manager for the Southern Pacific Company, the Union

Pacific System, and Oregon Short Line Railroad

(5).

Harriman controlled the Union Pacific, the Southern Pacific,

the Saint Joseph and Grand Island, the Illinois Central, the

Central of Georgia, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, and

the Wells Fargo Express Company, among other things. In

1906, Stohr was one of three men considered for the

promotion to Traffic Manager (Second Vice President), second

only to Mr. Harriman (6). He was not

promoted, and continued as Assistant Traffic Manager with

the Harriman organization until his death in 1912

(7).

It is hard to imagine today, the city

expanding North "toward" the corner of Wilson and

Evanston (Broadway), which is just a few blocks West

of Lincoln Park. But at the turn of the century, Wilson was

the end of the line. In 1900, the Northwestern Elevated

Railroad ended at Wilson Avenue. Farms could still be seen

from the elevated platform. The population continued to

expand North, and in 1908 the track was extended to meet the

demand. With Peter’s involvement with the railway, and

knowledge of the property involved, he saw an opportunity in

a piece of property which was most likely owned by the

railroad. In 1908 he signed a 35 year leased for the 120 by

320 foot triangular site and set out to improve the site

with stores and offices. There were many challenges, not the

least of which was the fact that a great part of the

property lay under the elevated tracks. Not much is known

about Stohr’s knowledge or relationship to Wright, but

working for one of the wealthiest businessmen in the

country, and coming in contact with men of that caliber, it

is hard to image that Wright’s name did not come up.

Like many, he may have admired Wright’s work at the time.

The Unity Temple, Oak Park, 1904. The Rookery Building,

Interior, Chicago, 1905. The Robie Residence, Chicago, 1906.

The Coonley Residence, Riverside, 1907. Browne's Bookstore,

Chicago, 1908. The City National Bank and Park Inn Hotel,

Mason City, IA 1909. These are just a few of the more

prominent buildings that Stohr might have seen and known

about.

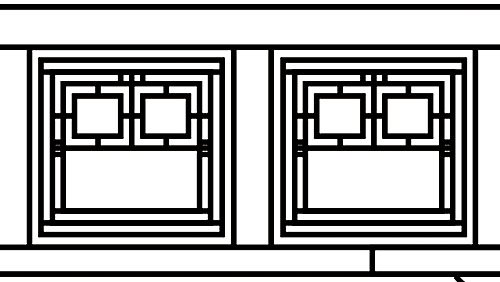

Not only was it a

triangular piece of property, but a majority of the property

was situated under the elevated tracks. Wright |

|

had to incorporate the steel

girders from the tracks above. He took advantage of the

Southeast corner which came out from under the tracks, and

designed a three story section. The length of the building

consisted of a row of shops and offices that opened up into

a Mezzanine. Hence, the Stohr Arcade. The second floor

design, is almost reminiscent of the Gale Residence (1904,

Oak Park, S.098), and the third floor is consistent with

Wright’s Oak Park Prairie style designs. The flat roof was

reinforced concrete. The chimney extends twelve feet above

the roof line. Wright designed large geometric vases

placed atop integrated pedestals, and continuous window

boxes for planting. He also designed cube and sphere

lighting fixtures that topped integrated pedestals at the

corner entrance. There exists no photographic evidence that

the vases were ever added, but a form of the light fixtures

were installed above the Southeast corner on the roof of the

first level as designed.

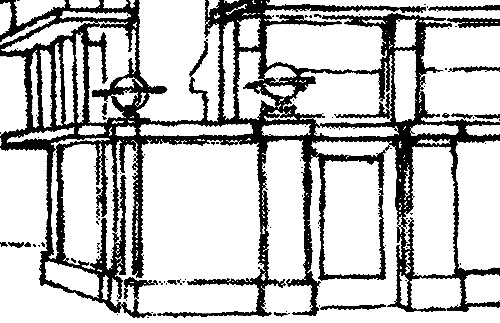

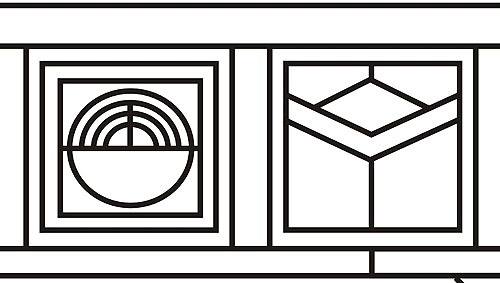

There are design themes that are

reminiscent of the Robie House designed three years earlier

(S.127) (1906). The proposed vase is the same as the Robie

House vase. One design for the entrance light fixtures are a

variation of the Robie House Living Room fixtures, but

mounted at the bottom instead of the side. No

cantilevered roof, but the building is anchored to the

ground by placing it on an enlarged concrete base.

There are consistent horizontal bands, and the third floor

is offset in much the same way. There is a row of

horizontal windows directly below the roof on the third

floor. And one of the proposed window concepts is an

adaptation of the geometric design of the Robie windows.

The most unique elements of this design are

the second floor windows. Like the Zimmerman Living Room

windows, this design is never used again. Although there are

a few examples of semi circular windows and many arched

doorways, the vast majority of windows were always

rectangular. The second floor window design consisted of

large windows topped by an arched circular curve. The glass

was divided vertically by a single mullion, and three

horizontally curved mullions. It was not until 1948 in the

Sol Friedman Residence (S.316) that he designed curved

windows. And again in 1956, a variation with the

Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church (S.399).

This may be the first example of Wright's

use of mitered corners. The street level has at lease two

visible examples. Wright designed many corner windows up to this point, but never mitered corners.

He expanded the use of mitered corners in the Freeman

Residence (S216) (1923). They became

prevalent, almost a trade mark in his later work. When

Wright left for Europe, he turned over the responsibility of

finishing the work on the Stohr Arcade on September 22, 1909

to Herman Von Holst who worked in his office

(9).

Just three years after the Stohr Arcade was

completed, obituaries reported on April 25, 1912 that after

a weeks illness Peter C. Stohr passed away in his home

(7). He was at the early age of 53. The Chicago

Blue Book of 1912 listed his address at the time as 1367 N.

State Street in Chicago (8).

During the late teens or very early 1920s,

an addition was added to the Southeast corner. The

addition can be seen in the December 1922 photographs of the

demolition. It enclosed the mitered glass corner, the

glass light fixtures and incorporated a new clock. Sadly in

1922, just 13 years after it was built, the Peter C. Stohr

Arcade Building was demolished to make way for expanded

service. It was replaced by a "White City" styled station.

Text by Douglas M. Steiner, Copyright

May 2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

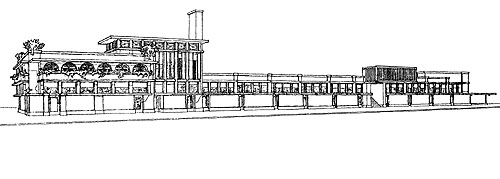

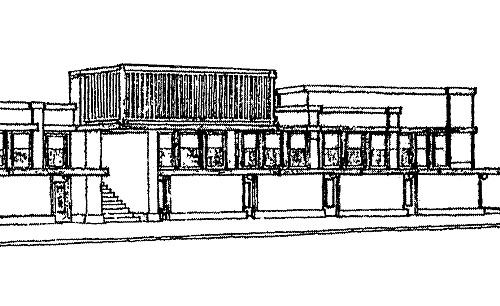

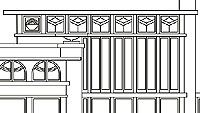

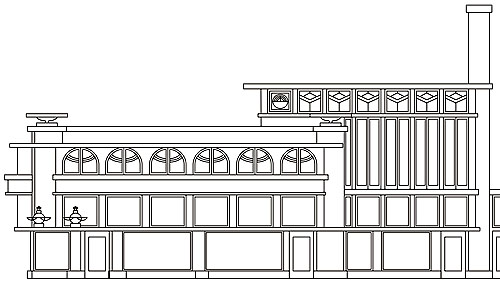

Stohr Arcade Building

Presentation Drawing, 1909 |

|

|

|

|

|

Not only was it

a triangular piece of property, but a majority of the

property was situated under the elevated tracks. Wright had

to incorporate the steel girders from the tracks above. He

took advantage of the Southeast corner which came out from

under the tracks, and designed a three story section. The

length of the building consisted of a row of shops and

offices that opened up into a Mezzanine. Hence, the Stohr

Arcade. The second floor design, is almost reminiscent of

the Gale Residence (1904, Oak Park, S.098), and the third

floor is consistent with Wright’s |

|

Oak Park Prairie style designs.

The flat roof was reinforced

concrete. The chimney extends twelve feet above the roof

line. Wright designed large geometric vases placed atop

integrated pedestals, and continuous window boxes for

planting. He also designed cube and sphere lighting fixtures

that topped integrated pedestals at the corner entrance.

There exists no photographic evidence that the vases were

ever added, but a form of the light fixtures were installed

on the Southeast corner on the roof of the first level as

designed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

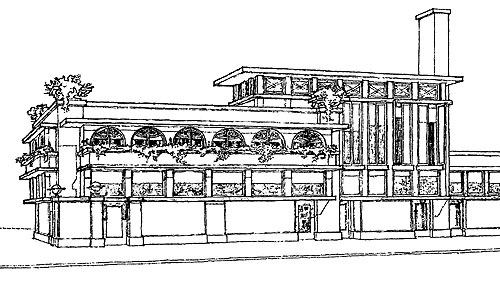

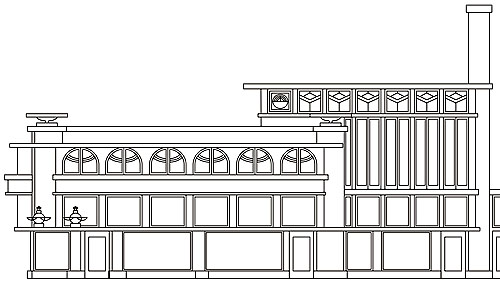

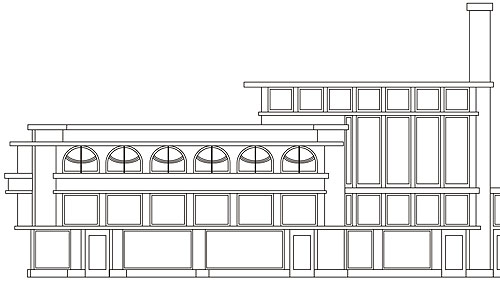

Stohr Arcade Building

Drawings, 1909 |

|

|

|

Proposed Drawing

Drawing of Completed Building |

|

|

|

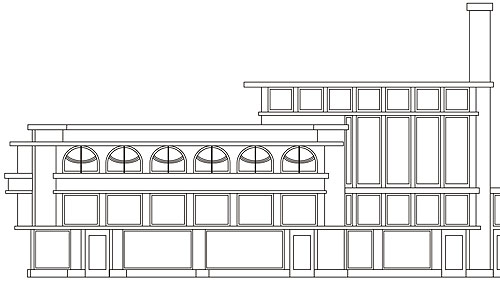

The Stohr Arcade was a

beautifully designed building. There are design themes that are

reminiscent of the Robie House designed three years earlier

(S.127) (1906). The proposed vase is the same as the Robie

House vase. One design for the entrance light fixtures are a

variation of the Robie House Living Room fixtures, but

mounted at the bottom instead of the side. No

cantilevered roof, but the building is anchored to the

ground by placing it on an enlarged concrete base.

There are consistent horizontal bands, |

|

and the third floor is offset in much the same way. There is a row of

horizontal windows directly below the roof on the third

floor. And one of the proposed window concepts is an

adaptation of the geometric design of the Robie windows. The

chimney extends twelve feet above the roof line.

Illustrations were drawn from originals by Douglas M. Steiner and are a close

representation. |

|

|

|

|

Proposed Drawings of

the Peter C. Stohr Arcade |

|

|

Proposed design elements:

The proposed vase for the Stohr Arcade is the same as the Robie

House vase. The building is anchored to the

ground by placing it on an enlarged concrete base. There is a row of

horizontal windows directly below the roof on the third

floor. And one of the proposed window concepts is an

adaptation of the geometric design of the Robie windows. The

chimney extends twelve feet above the roof line. |

|

|

|

|

|

See additional illustrations. |

|

|

|

Drawings of the

Completed Peter C. Stohr Arcade |

|

| Actual design

elements: There exists no photographic evidence that vases were

ever added, but a form of the light fixtures were installed on the

Southeast corner on the roof of the first level as designed. Most of

the decorative windows were eliminated, possibly due to cost

constraints, but the arched windows were installed.. The chimney

extends twelve feet above the roof line. |

| |

|

Illustrations were drawn from

originals by Douglas M. Steiner and are a close representation.

Copyright 2009. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

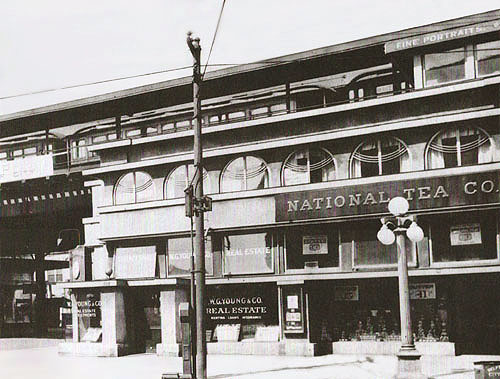

Historic Photographs

of the Stohr Arcade Building |

|

|

|

|

|

Not only was it a triangular

piece of property, but a majority of the property was

situated under the elevated tracks. Wright had to

incorporate the steel girders from the tracks above. He took

advantage of the Southeast corner which came out from under

the tracks, and designed a three story section. The length

of the building consisted of a row of shops and offices that

opened up into a Mezzanine. Hence, the Stohr Arcade. The second floor

design, is almost reminiscent of the Gale Residence (1904,

Oak Park, S.098), and the third floor is consistent with

Wright’s

|

|

Oak Park Prairie style designs.

The flat roof was reinforced concrete. The chimney

extends twelve feet above the roof line. Wright designed

large geometric vases placed atop integrated pedestals, and

continuous window boxes for planting. He also designed cube

and sphere lighting fixtures that topped integrated

pedestals at the corner entrance. There exists no

photographic evidence that the vases were ever added, but a

form of the light fixtures were installed above the

Southeast corner on the roof of the first level as designed. |

| |

|

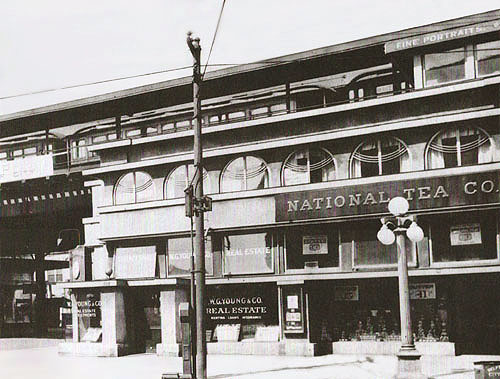

Stohr Arcade Building Circa

1914 |

|

|

Courtesy of the Krambles-Peterson Archives |

|

|

View looking North down Evanston

(Broadway). Just a few years after the building has been

completed. Wright took advantage of the Southeast corner

which came out from under the tracks, and designed a three

story section. |

| |

|

|

Detail of above image. View

looking North down Evanston (Broadway). Wilson Avenue runs

East and West. Just a few years after the building has

been completed. Wright took advantage of the Southeast

corner which came out from under the tracks, and designed a

three story section. |

| |

|

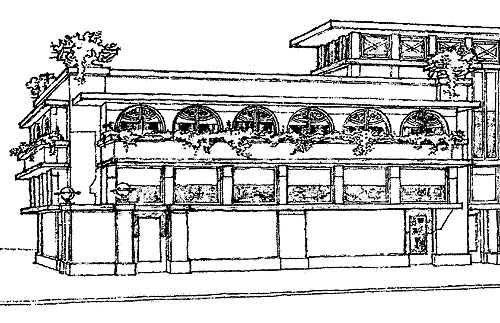

Stohr Arcade Building Circa

1917 |

|

|

Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society |

|

|

Viewed from the Northeast. A

form of the light fixture Wright designed is visible above

the Southeast corner on the roof of the first level. Large

windows at the top of the first floor allow light into the

interior and swing open at the bottom allowing air to

naturally cool the building. The second floor window design

consisting of large arched curves which were unique only in

this Wright building. |

| |

|

|

Courtesy of the Krambles-Peterson Archives |

|

|

Viewed from the Northeast. On

the far left, the Southeast corner of the street level, the

mitered glass corner is visible. This may be the first

example of Wright's use of mitered corners. The street level

has at lease two visible examples. The large sets of

vertical windows on the right cover two floors. |

|

|

|

See Additional details. |

|

Text by Douglas M. Steiner, Copyright

2009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Destruction

of the Stohr Arcade Building

1922 |

|

|

|

|

|

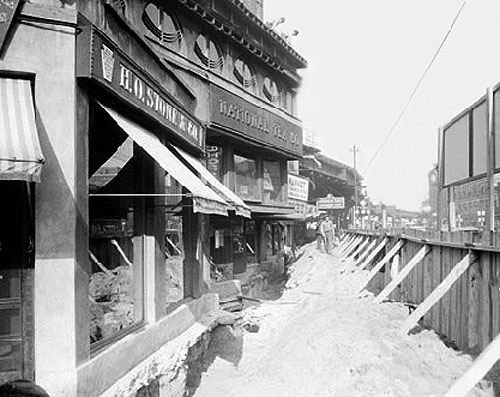

During the late teens or very

early 1920s, an addition was added to the Southeast corner.

The addition can be seen in the December 1922 photographs of

the demolition. It enclosed the mitered glass corner,

the glass light fixtures and incorporated |

|

a new clock.

Sadly in 1922, just 13 years after it was built, the Peter

C. Stohr

Arcade Building was demolished to make way for expanded

service. It was replaced by a "White City" styled station. |

|

|

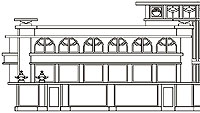

The Stohr Arcade Building

Replaced 1923 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sadly in 1922, just 13 years

after it was built, the Peter C. Stohr

Arcade Building was demolished to make way for expanded

|

|

service. It was replaced by a "White City" styled station

designed by architect Arthur U. Gerber. |

|

|

|

|

Courtesy of the Krambles-Peterson Archives |

|

| View

looking North down Broadway. Just 13 years after it was

built, the Peter C. Stohr

Arcade Building was demolished to make way for expanded

service. It was replaced by a "White City" styled station

designed by architect Arthur U. Gerber. |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

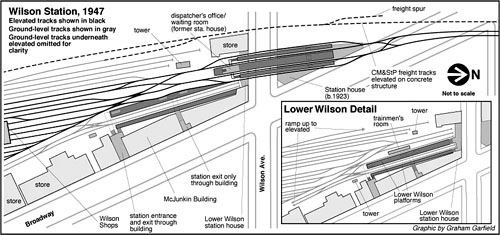

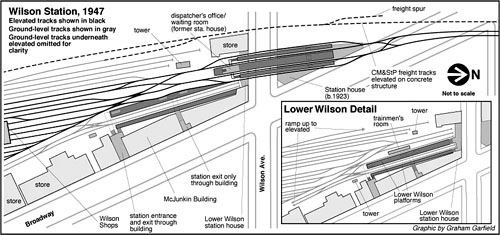

Wilson Station Track

Map 1947 |

|

|

Courtesy of Fast & Faster |

|

|

Although this map depicts 1947, it is

a representation of where the building was located. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related

Items |

|

|

|

Date: Circa 1917

Title:

Peter C. Stohr Arcade Building, Chicago circa 1917 (1909 -

S.162).

Description:

Designed in 1909, it was demolished in 1922, just 13 years after

it was built. Viewed from the Northeast. A form of the light

fixture Wright designed, or what is left of it, is visible above

the Southeast corner on the roof of the first level. Large

windows at the top of the first floor allow light into the

interior and swing open at the bottom allowing air to naturally

cool the building. The second floor window design consisting of

large arched curves which were unique only in this Wright

building. Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society.

Size:

10 x 7 B&W photograph.

S#: 0138.09.0115 |

|

|

|

|

Date: Circa 1917

Title:

Peter C. Stohr Arcade Building, Chicago circa 1917 (1909 -

S.162).

Description:

Designed in 1909, it was demolished in 1922, just 13 years after

it was built. Viewed from the Northeast. On the far left, the

Southeast corner of the street level, the mitered glass corner

is visible. The second is in the center, just to the right of

the gentleman window shopping. This may be the first example of

Wright's use of mitered corners. A form of the light fixture

Wright designed is visible above the Southeast corner on the

roof of the first level. The large sets of vertical windows on

the right cover two floors. The large vertical plate glass

windows are nearly twelve feet high. Courtesy of the Krambles-Peterson

Archives.

Size:

10 x 7 B&W photograph.

S#: 0138.10.0115 |

|

|

|

|

|

Date: 1922

Title:

Peter C. Stohr Arcade Building, Chicago 1922 (1909 - S.162).

Description:

Designed in 1909, it was demolished in 1922, just 13 years after

it was built. During the late teens or very early 1920s, an

addition was added to the Southeast corner. It enclosed the

mitered glass corner, the glass light fixtures and incorporated

a new clock. Courtesy of the CTA Collection.

Size:

10 x 5 B&W photograph.

S#: 0147.08.0115 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Related Books |

|

|

| (1)

"New York Times" October

13, 1887 |

| (2)

"The 1891 Grain Dealers and Shippers Gazetteer" Chicago, St.

Paul & Kansas City Railway System, Officers: P. C. Stohr, Title:

General Freight Agt., Chicago, Ill. |

| "The Official

Railway List; a Complete Directory" Page 59, P. C.

Stohr , General Freight Agt., Chicago, Ill. |

| (3)

"Annual Report of the Railroad and Warehouse

Commissioners of the State of Missouri, 1897" Letter A) St.

Paul, Minn., March 16, 1897, P.C. Stohr, G.F.A, Letter B) March 27,

1897, P. C. Stohr, General Freight Agent. |

| "Annual Report

of the Board of Railroad Commissioners, for the Year Ending 1898",

Chicago Great Western Railway Company, Officer: P. C. Stohr,

General Freight Agent, St. Paul, Minn office. |

| (4)

"Annual Report of the Railroad and Warehouse Commission of the

State of Illinois For 1901" Page 28, 225. Chicago Great

Western Railway Company, Officer: P. C. Stohr, Traffic Manager, St.

Paul, Minn office. |

| "Report of the

Board of Railroad Commissioners, State of Kansas, for the year

ending 1902" (Same for 1903 & 1904), Page 13,

Chicago Great Western Railway Company, Officer: P. C. Stohr, Traffic

Manager, St. Paul, Minn. office. |

| (5)

"Poor's Directory of Railway Officials" Page 71, Southern

Pacific Company, Assistant Traffic Director: P.C. Stohr, Chicago,

Ill. And Page 78, Union Pacific System, Oregon Short Line RR,

Assistant Traffic Director: P.C. Stohr, Chicago, Ill. |

| (6)

"New York Times" Nov

16, 1906 (PDF) |

| "Annual Report

of the Board of Railroad Commissioners for the Year Ending 1907"

Page 209, Board of Railroad Commissioners, Officers: P.C. Stohr,

Assistant Traffic Director, Chicago, Ill. |

| "Reports of the

Railroad and Public Service Commissions of Nevada" Page 140,

Southern Pacific Company, Assistant Traffic Director: P.C. Stohr,

Chicago, Ill. |

| "Railway age

gazette" page 857. PC Stohr, Assistant Director of Traffic

of the Southern Pacific company, the Union Pacific, the Oregon Short

Line and the Oregon-Washington Railroad & Navigation Company, will

continue to have his office at Chicago, while the director of

traffic has had his office moved to New York City, as has been

announced in these columns. |

| (7)

"New York Times"

Obituary, April 26, 1912 |

| (8)

"The Chicago Blue

Book" of 1912, Page 271-272, Mr. & Mrs. Peter C. Stohr

& daughters, 1367 North State Street. |

|

"The

Nature of Materials: 1887 - 1941",

Hitchcock, 1942, page 53. |

|

"Frank Lloyd Wright

to 1910, The

First Golden Age"

Manson, 1958, pages 168-169. |

|

"Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph 1907-1913",

Vol. 3, Text: Pfeiffer, Bruce Brooks; Edited and Photographed: Futagawa,

Yukio, 1987, pages 124-125. |

| "The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion", Storrer, William Allin,

1993, page 165. |

|

"Frank Lloyd Wright

Architect", Riley, Reed, Alofsin, Cronon, Frampton,

Wright, 1994, page 163. |

|

"Lost

Wright",

Lind, 1996, page 142-143. |

| (9)

"Frank

Lloyd Wright - The Lost Years"

Alofsin, 1998, page 312. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CLICK TO ORDER